The Schoharie Kill

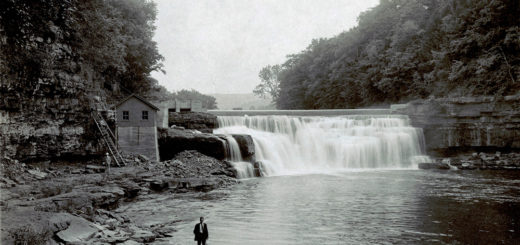

Well begun is half done, they used to say. As in the course of human events, so too with rivers. Make a good start and it’s downhill the rest of the way. Consider, for example, the Schoharie Kill, a beautiful creek with a dark reputation. Its headwaters—one of them anyway—is close by a lesser-traveled road in a remote corner of the town of Hunter. You could say it’s a non-descript spot, not marked on any map nor marred by any interpretive signage. The wellspring of the Schoharie remains a “terrain vague,” a roadside non-attraction—thus a good place to bury or dig for treasure. The Schoharie’s first historian described the headwaters as a “swamp back in the Blue Mountains.” Maybe it was so in 1823, but nowadays it’s not so much a swamp as a soggy patch of lawn bisected by a driveway leading to an erstwhile boardinghouse. From this unremarkable seat in the shadow of Indian Head Mountain rises one of the most remarkable—not to mention ornery—streams in all of the Catskill Mountains.

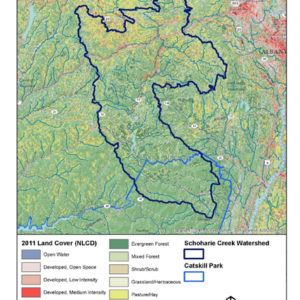

From its point of origin—just twelve miles west of the Hudson River—the Schoharie pursues a northwesterly course for twenty-five miles, skirting along the base of some of the loftiest mountains in the range—High Peak and Roundtop, Indian Head, Twin, Mink, Plateau, Hunter, Rusk, and Bearpen—before being impounded by New York City’s reservoir at Gilboa. After that, the Schoharie reclaims its freedom, swinging around in a northeasterly course and racing through less-elevated though equally formidable terrain for another fifty miles until it joins the Mohawk River at Fort Hunter. Along its ninety-three mile course, the main-stem of the Schoharie is fed by dozens and dozens of tributaries—including the East Kill, the West Kill, the Batavia Kill, and the Cobles Kill, just to name a few—gathering the abundant waters shed from the rumpled precincts of seven different counties.

From its point of origin—just twelve miles west of the Hudson River—the Schoharie pursues a northwesterly course for twenty-five miles, skirting along the base of some of the loftiest mountains in the range—High Peak and Roundtop, Indian Head, Twin, Mink, Plateau, Hunter, Rusk, and Bearpen—before being impounded by New York City’s reservoir at Gilboa. After that, the Schoharie reclaims its freedom, swinging around in a northeasterly course and racing through less-elevated though equally formidable terrain for another fifty miles until it joins the Mohawk River at Fort Hunter. Along its ninety-three mile course, the main-stem of the Schoharie is fed by dozens and dozens of tributaries—including the East Kill, the West Kill, the Batavia Kill, and the Cobles Kill, just to name a few—gathering the abundant waters shed from the rumpled precincts of seven different counties.

Most of the time, the Schoharie runs softly through woods and meadows, serving as inspiration to artist and angler and lover alike, giving no indication of the ferocity that a sudden turn in the weather will unleash. A hint, however, is lodged in the Mohawk origins of the name Schoharie: To-wos-scho-har, meaning “flood-wood.” Not any old flood-wood, but a very specific one. As the venerable Jeptha Simms explains in his authoritative history of Schoharie County, this flood-wood was deposited across a wide stretch of the creek just upstream from the present village of Middleburgh, where “two small streams run into the river directly opposite each other.” The convergence of waters generated a countercurrent on the main stream, “which  caused a lodgment of driftwood, at every high water, directly above. The banks of the river there were, no doubt, studded, at that period, with heavy growing timber, which served as abutments for the formation of a natural bridge. I judge so from the fact, that between that place and the bridge below, on the west bank, may now be seen a row of elm stumps of gigantic growth. At the time the Indians located in the valley, who were the owners of the soil when the Germans and Dutch first settled there, tradition says there were thousands of loads of wood in the wooden pyramid. How far it extended on the flats on either side is uncertain, they being at that place uncommonly wide; but across the river, it is said to have been higher than a house of ordinary dimensions, and to have served the natives the purposes of a bridge, who, when crossing, could not see the water through it.” Back in those days the Schoharie gaveth a bridge. Since then it only taketh them away.

caused a lodgment of driftwood, at every high water, directly above. The banks of the river there were, no doubt, studded, at that period, with heavy growing timber, which served as abutments for the formation of a natural bridge. I judge so from the fact, that between that place and the bridge below, on the west bank, may now be seen a row of elm stumps of gigantic growth. At the time the Indians located in the valley, who were the owners of the soil when the Germans and Dutch first settled there, tradition says there were thousands of loads of wood in the wooden pyramid. How far it extended on the flats on either side is uncertain, they being at that place uncommonly wide; but across the river, it is said to have been higher than a house of ordinary dimensions, and to have served the natives the purposes of a bridge, who, when crossing, could not see the water through it.” Back in those days the Schoharie gaveth a bridge. Since then it only taketh them away.

Thanks to topography and climate, the Schoharie watershed has always been prone to flooding. John M. Brown—the aforementioned first historian—reports that the Indians in the area had carved out a stump and erected a cairn of stones to mark the creek’s known high water mark during flooding. European settlers arriving in 1713 proceeded to settle “within a hundred yards of this stump block or boundary,” despite being told what the marker signified. It “was never believed by white men that the Indians had seen water there[,] until the year 1784 and 1785, when they witnessed the flood, which had risen four or five feet above the monument of the stump block.” Those eighteenth century floods proved to be harbingers.

European patterns of settlement—which included the widespread removal of forest—were responsible for catastrophic increases in the amount of runoff. A visitor in 1904 observed what by then had become a common sight: “The Schoharie is a long creek, and it has its headsprings far up among  the mountains, and some bright summer afternoon the thunder clouds gather around the Catskills, and then by and by swiftly covering all the dusty creek bed comes a roaring flood of brick-red water, and sometimes the flood increases until the soft red soil which took unnumbered thousands of years to accumulate begins to melt away like so much sugar, and the farmer must stand helplessly by and watch land that he has been brought up to think of as worth $200 per acre go to make work for the contractors that dredge the Hudson River, leaving his deed covering only a barren, desolate waste of boulders and gravel, which nature in the course of years, with all her efforts, succeeds in covering with only a scanty growth of hardy willows and sweet clover. Farms have thus lost twenty acres in a single night, and keeping up the protecting belts of trees and diking the banks with cedar brush overlain with stone is one of the regular arts of the farmer. They are face to face with the geologic law that all streams are migratory and love to change their beds.”

the mountains, and some bright summer afternoon the thunder clouds gather around the Catskills, and then by and by swiftly covering all the dusty creek bed comes a roaring flood of brick-red water, and sometimes the flood increases until the soft red soil which took unnumbered thousands of years to accumulate begins to melt away like so much sugar, and the farmer must stand helplessly by and watch land that he has been brought up to think of as worth $200 per acre go to make work for the contractors that dredge the Hudson River, leaving his deed covering only a barren, desolate waste of boulders and gravel, which nature in the course of years, with all her efforts, succeeds in covering with only a scanty growth of hardy willows and sweet clover. Farms have thus lost twenty acres in a single night, and keeping up the protecting belts of trees and diking the banks with cedar brush overlain with stone is one of the regular arts of the farmer. They are face to face with the geologic law that all streams are migratory and love to change their beds.”

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the magnitude and frequency of flooding in the Schoharie watershed increased dramatically, a trend that continued through the twentieth and now into the twenty-first century. Flood records kept by the National Weather Service in Albany provide a trove of hydrological horrors. Among the highlights:

- October 1955: “Severe flooding on the Schoharie Creek caused by a slow-moving coastal storm which produced 16 to 18 inches of rainfall over the Tannersville area and devastation in the Schoharie Valley.”

- March 1980: “‘The Great Catskill Toilet Flush’ with around 10 inches of rain on nearly bare and frozen ground which led to rapidly developing and severe floods on Schoharie, Catskill, and Esopus Creeks. A fatality occurred when a motorist ignored a roadblock.”

- April 4-6, 1987: “Snowmelt and large rainfall amounts led to severe flooding on the Mohawk River and in the Catskills. On the morning of April 5, the New York State Thruway Bridge over the Schoharie Creek suddenly collapsed. At least 10 people died when their vehicles plunged into the flood swollen creek.”

- January 19-20, 1996: “The Northeast Floods of January 1996 were the result of a very rapid snowmelt punctuated by a short but intense rainfall; 2 to 4 inches of rain. What made this event so unusual was the nature and the intensity of the snowmelt, combined with the intense rainfall for this time of year, over such a large geographical area. The flooding was compounded by ice movement and jamming in many of the rivers and streams. Record flooding on Schoharie Creek.”

- September 30-October 1, 2010: “The remnants of Tropical Storm Nicole moved northward along a nearly stationary boundary along the east coast bringing abundant tropical moisture into the region. Major flooding occurred on the Esopus Creek at Cold Brook and on the Schoharie Creek at Prattsville.”

- August 28, 2011: “Tropical Storm Irene.” Memory will serve to fill in the grim details for that one.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on March 22, 2019