Poet’s Ledge

By John P. O’Grady

At the annual exhibition of the National Academy of Design in 1861, Sanford Robinson Gifford’s latest artwork was hailed as “the great picture of the season, the crowning glory of the exhibition.” Another declared it “one of the most original and admirable delineations of our scenery yet produced.” The New York Daily Tribune chimed in: “The brilliance of this picture almost fills the room, and we doubt if any one enters without his eyes being attracted involuntarily to the spot.” According to The Crayon: “The point of view is well selected and the scene is well adapted to the hour at which we view it in the picture.” The title of this painting was A Twilight in the Catskills—and it secured Gifford’s reputation as a landscape artist, elevating him to the ranks of Thomas Cole and Frederic Church.

The picture was immediately purchased by John Bundy Brown, who at the time was the wealthiest man in the State of Maine. After Gifford’s untimely death in 1880, his much acclaimed Twilight drops from public view for more than a century. Whenever art historians of the twentieth century referred to it, they employed the doleful attributive of “lost.” One could easily imagine the canvas having been committed to some dusty attic along with the forgotten furniture and wardrobes of yesteryear. Then one day in 1998, the sizeable canvas of A Twilight in the Catskills (it measures 27 x 54 inches) unexpectedly reappeared. It had been brought in to the Williamstown Art Conservation Center for a little TLC. In the words of one of the conservators: “The painting had gone unrecognized in a basement for years.” As might be expected, the decades had taken their toll on the painting. It “exhibited a number of physical and cosmetic problems, partly owing to vices inherent in Gifford’s execution methods.” Apparently the artist, in planning and carrying out his masterwork, had not anticipated that it would be hung in a dank New England cellar. But that’s all behind us now. The painting has been restored to its former glory—or rather, its incandescent gloom—and hangs in Yale University’s climate-controlled art gallery.

If you can’t make your way to New Haven to see Twilight for yourself, a fine image of it is available online. Call it up on your monitor and you’ll enter an otherworldly scene steeped in the lurid glow of a recently departed sun. Before your eyes is an expansive, dimly-lit gorge, recognizable as Kaaterskill Clove. Through its labyrinthine depths winds a serpentine creek that doesn’t so much flow as smolder. Distant mountains rim the horizon. A lowering bank of clouds hangs overhead. The individual trees that frame the view are blasted and woebegone. A Stygian stream in the immediate foreground leads your eye toward an apparent precipice and abyss. The only sign of life seen in the funereal solitude is a black bear—or is it a cub?—hardly discernable, in the lee of a boulder situated in the lower left foreground. Diminutive as it appears in the foreboding vastness, this bear—once perceived—arrests your attention. It becomes the most unsettling element in a most unsettling scene. In the face of such measureless isolation, you become uncertain whether to fear more for the bear or for yourself. Oh well, that’s what art often does: it unsettles.

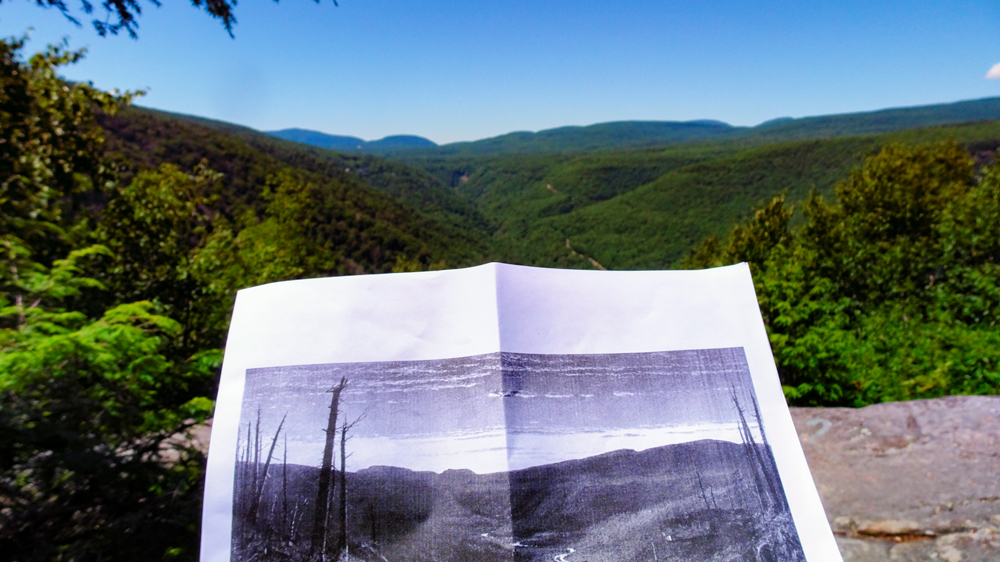

Surprising then to learn that Gifford’s inspiration for the ominous spectacle of A Twilight in the Catskills arrived under rather pleasant circumstances. On a fine summer’s day in July of 1860, the artist made his way with companions to a rocky outcrop high on the less-frequented south wall of Kaaterskill Clove and did some sketching. It’s a place today known as Poet’s Ledge. Gifford—who was raised just across the river in the city of Hudson—loved the Catskill Mountains. He was an inveterate hiker and wilderness explorer, the clove being one of his favorite haunts. More often than not, he was joined on his mountain excursions by his good friends and fellow landscape artists Jervis McEntee and Worthington Whittredge. As Whittredge recalled in later years, when Gifford was out in the wilds of the mountains he would “frequently stop in his tracks to make slight sketches in pencil in a small book which he always carried in his pocket, and then pass on, always suspicious that if he stopped too long to look in one direction the most beautiful thing of all might pass him by at his back.” Gifford liked to refer to this practice as “air painting.” The sketch he made that day at Poet’s Ledge survives, though in very degraded condition. Even so, the drawing as well as the painting—created the following winter at the artist’s studio in Manhattan—are remarkable for their fidelity to the local geography. Each slope and recess in Kaaterskill Clove is rendered true to life. One familiar with the locale immediately recognizes the forms of the distant mountains: Onteora, Parker, and West Stoppel Point, with the summit of Black Dome just peeking above an ascending ridge. The only element found in the painting that is missing in the sketch and on the ground at Poet’s Ledge is the stream and implied waterfall, which seem to be items Gifford borrowed from sketches made previously at the brink of Kaaterskill Falls. But hey, one must grant the artist a bit of license. After all, this is a painting, a work of art, not a documentary illustration.

After spending so much time with Gifford’s painting, I felt the need to revisit Poet’s Ledge. I hadn’t been there in a few years. Wanting to learn something about the history of the place , I consulted several learned sources but came up with little information—and only a single mention of the fact that Poet’s Ledge provided the inspiration for A Twilight in the Catskills. I did happen upon one mountain enthusiast’s online post about certain dangers the casual visitor might face at Poet’s Ledge: “There is a benign looking crack in the ledge,” he reports. “If you look carefully, there is a 30’ drop into a cave. If you fall thru the crack, I don’t know if you can get out, or if you will encounter a sleeping bear. So, use caution. The best time to arrive at Poet’s Ledge is around noon time to 2 PM in the afternoon. Late in the afternoon is the worst time. Arriving too early in the morning increases the probability of a bear encounter. It takes 2 hours and 15 minutes to get there.”

The other day, I walked to Poet’s Ledge and arrived late in the afternoon. It took me less than two hours to get there. It was a warm July day. The sun was shining and so were the mountains. From below arose the roar of motorcycle engines and other traffic along the Mountain Road through the clove. I stood on the precipice where Gifford had made his sketch. Emblazoned in pale blue spray-paint on the rock upon which I stood was the signature of a late visitor, an artist of another kind, I suppose. I took some pictures of the scenery and was mindful of the crack. I did not want to fall into any cave. I made it home safely, well before twilight set in. Coming and going to Poet’s Ledge I saw no one, not even a bear.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on July 13, 2018