An Artist’s Studio in Rondout

Hudson River School artist Jervis McEntee was born in the village of Rondout, New York in 1828. His father, James, was an engineer and prominent citizen in the community. In 1848, the elder McEntee purchased 52 acres of undeveloped land on Weinbergh Hill, overlooking the Hudson River. His was an eye that made estates, not landscapes. He laid out a street on the northwest slope and subdivided the property into several building lots. These he sold off to other prominent citizens, who in time erected sizeable houses. James reserved the crown of the hill for himself, where he erected his own sizeable house. This place came to be known as the McEntee family homestead.

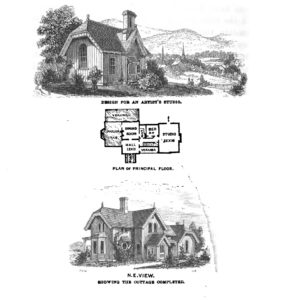

Jervis, the engineer’s son, was drawn—despite paternal disapproval—to a career in art and became a student of the renowned landscape painter Frederic Church. The naturally gifted McEntee enjoyed a bit of early success in the New York art scene of the 1850s. His paintings were well-received by fellow artists and critics alike. He made a number of sales to the men and women of wealth, upon whom artists so often depend. In 1860, young McEntee was elected to the National Academy of Design. At some point in the 1850s, he commissioned his brother-in-law, the architect Calvert Vaux, to design a small artist studio to be built on the McEntee family homestead, not far from his father’s house. A few years later, he had his brother-in-law add modest living quarters to the studio. It was here that McEntee and his wife, Gertrude, spent their summers for the next two decades and more, until her death in 1878. As described by Vaux in his 1857 book, Villas and Cottages, the McEntees’ home “is finely placed on an elevated site, and commands an extended view of the Kaatskills and the Hudson.”

enjoyed a bit of early success in the New York art scene of the 1850s. His paintings were well-received by fellow artists and critics alike. He made a number of sales to the men and women of wealth, upon whom artists so often depend. In 1860, young McEntee was elected to the National Academy of Design. At some point in the 1850s, he commissioned his brother-in-law, the architect Calvert Vaux, to design a small artist studio to be built on the McEntee family homestead, not far from his father’s house. A few years later, he had his brother-in-law add modest living quarters to the studio. It was here that McEntee and his wife, Gertrude, spent their summers for the next two decades and more, until her death in 1878. As described by Vaux in his 1857 book, Villas and Cottages, the McEntees’ home “is finely placed on an elevated site, and commands an extended view of the Kaatskills and the Hudson.”

In 1858, McEntee painted a charming little tondo of his home/studio as it appeared in apple blossom time. Fourteen years later, he was drawn to paint these trees again. He writes about it in his diary. “The Apple trees are in the full glory of blossoms now and from day to day the landscape freshens visibly. It is difficult to realize the grey of a week ago. I made a sketch from my window this morning looking towards Hussey’s Hill with blooming apple trees in the foreground. It was not very successful but will serve as a memorandum.” In later years, McEntee captured the glory of a summer sunset on the Great Wall of Manitou, also as seen from his studio window. Art historians have noted the bright colors used to depict these spring and summer scenes are atypical for this artist whose chief subject was the landscape of late fall and early winter, paintings in which the tones are somber and the effects melancholic. Even so, to judge from these pictures and the diaries he kept from 1872 till close to his death in 1891, McEntee deeply loved the family homestead on Weinbergh Hill.

In 1858, McEntee painted a charming little tondo of his home/studio as it appeared in apple blossom time. Fourteen years later, he was drawn to paint these trees again. He writes about it in his diary. “The Apple trees are in the full glory of blossoms now and from day to day the landscape freshens visibly. It is difficult to realize the grey of a week ago. I made a sketch from my window this morning looking towards Hussey’s Hill with blooming apple trees in the foreground. It was not very successful but will serve as a memorandum.” In later years, McEntee captured the glory of a summer sunset on the Great Wall of Manitou, also as seen from his studio window. Art historians have noted the bright colors used to depict these spring and summer scenes are atypical for this artist whose chief subject was the landscape of late fall and early winter, paintings in which the tones are somber and the effects melancholic. Even so, to judge from these pictures and the diaries he kept from 1872 till close to his death in 1891, McEntee deeply loved the family homestead on Weinbergh Hill.

Despite his early success in the art world, McEntee began to have difficulties selling his paintings after the Civil War. By the 1870s, tastes in the New York market were changing. Preferences were shifting away from Hudson River School landscapes toward new European styles of painting. None of this sat well with McEntee—and it took a toll on him both emotionally and financially. In 1872, he laments in his diary: “foreign Art and foreign pictures are pouring in in a perfect deluge. There seems no place for us but I hope it will be good for us in some way.” On his birthday that same year he writes: “Sometimes I doubt if an artistic temperament is compatible with the happiest and serenest life, for while the satisfactions are often great, how many inexpressible longings there are which will not shape themselves.” Two years later he vents: “Another thing which I have always insisted on is that artists should always stand up for the dignity of their profession and not quietly listen to the conceited utterances of ignorant

people who presume to set themselves up as authorities the moment they buy a few pictures. I have met with instances of this kind which were too offensive to be borne and have incurred the charge of being a churlish fellow because I would not quietly listen to it.” On his sixtieth birthday, he writes: “Life is not as attractive as it ought to be. My profession does not yield me the satisfaction I hoped it would when most other of life’s attractions failed. I find I grow to absolutely dread responsibility and long only for quiet and congenial companionship with my peculiar temperament, unable to make new friends I dread the loneliness of the future, should I live, when the old friends are gone.” And in 1890, he looks around at the National Academy and despairs over the “great throng of aggressive looking young men” who were now the celebrities of the art world. Nobody wanted to buy his pictures anymore. “The whole thing comes upon me and I am utterly powerless to raise any money except by selling something, of which there seems no prospect. The outlook is most discouraging and I have again entered upon the gnawing and wearing anxieties which have pressured me through so many years of my life.” One comes away from McEntee’s diaries with the distinct impression that art-making can be a deleterious profession.

Faced with mounting debt and the frailties of age, the artist had no choice but to sell off most of the remaining lots on the McEntee family homestead—including his beloved house and studio designed by Vaux. Samuel D. Coykendall—at the time, the wealthiest and most powerful man in Ulster County—purchased the property for $22,500. He wasted no time in removing the old studio, putting up in its place an imposing redbrick mansion that stood upon the crest of Weinbergh Hill until 1950, when it met a fate in kind: torn down and replaced by a modest development of ranch houses. The triumphs of industry, alas, are often in close proximity to those of art, as are the falls. No historic markers or signage commemorate the site of Jervis McEntee’s studio or Coykendall’s stately mansion. The views obtained there today are from the sidewalk. One must peer into the gaps between suburban houses.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on July 6, 2018