Maverick Concert Hall

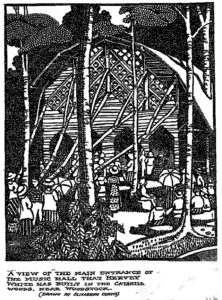

The Maverick Concert Hall still stands in the isolate woods just north of the drowned towns of the Ashokan Reservoir. Built over a ten year period by poet-philosopher Hervey White, the Maverick opened its doors more than a century ago, on July 30, 1916. “Music Goes Back to Nature!” proclaimed the headline in the New York Times. “From all the nearby Catskill summering places, and from some at a considerable distance, people are coming to the music chapel that Mr. White has built on his farm in the Woodstock Valley to hear the eminent musicians Mr. White has gathered play the best chamber music, which he selects himself.” The music hall resembles a rustic barn, fronted with a conspicuous array of diagonal windows above four large doors that open upon an outdoor listening area. On one side of the structure, a large oak tree thrusts its way up through the mossy roof. Immediately to the west rises the steep, forested slope of Ohayo Mountain. “Chamber music,” declared Hervey White, “by its nature, is degraded except when it is given by selected musicians in a rustic music chapel among tall trees at the foot of a hill.” He must have been on to something. The inaugural season of concerts was a great success. Over the following years, the Maverick gained a reputation for excellence as a venue and drew prominent musicians from all over the world. Today Maverick Concerts is the oldest continuous summer chamber music festival in America, having just concluded its 103rd season. Except for those two busy months every summer, the Maverick is a rather quiet and out-of-the-way place, not easy to find. A middle-of-nowhere that wants to stay that way.

The most famous performance ever to take place at the Maverick occurred on August 29, 1952. On that evening, the composer John Cage premiered his now-legendary “silent piece,” more commonly known as 4′33″—because that’s how long it takes to perform. A three movement composition, it was played by pianist David Tudor. The performance went like this. The house was packed. Tudor—formally dressed, as would be expected under such dignified circumstances—took his place at the piano bench. He set out a stopwatch and closed the keyboard lid. He studied the musical score and did not move. The audience remained politely quiet. After thirty seconds, Tudor raised the keyboard lid and looked at the stopwatch. Again he closed the lid, studied the score, and did not move. During this interval a gust of wind blew in through the open doors and spacious gaps between the wall boards. Rain could be heard pattering on the roof. After two minutes and twenty-three seconds had passed, Tudor again raised the keyboard lid and looked at the stopwatch. Again he closed the keyboard lid and studied the score. By this point, the audience had begun to lose patience. Many were muttering and rustling in their seats. After one minute and forty seconds had passed, Tudor stood up and walked off the stage. Performance over. That’s when all hell—or what passes for it among devotees of chamber music—broke loose. Somebody in the audience stood up on his chair and shouted: “Good people of Woodstock, let’s run these villains out of town!” Decades later, John Cage recalled what happened that evening: “People began whispering to one another, and some began to walk out. They didn’t laugh—they were irritated when they realized nothing was going to happen, and they haven’t forgotten it thirty years later: they’re still angry.” Later he added: “I had friends whose friendship I valued and whose friendship I lost because of that night.”

Nowadays we might wonder: Why all the fuss? Why get so upset over a little silence? Cage accounted for it by saying the audience had “missed the point. There’s no such thing as silence. What they thought was silence in 4′33″—because they didn’t know how to listen—was full of accidental sounds.” Audience expectations had been thwarted. Instead of chamber music, they were presented with the music of the world, breaking upon them from both inside and outside the concert hall. They heard coughs instead of notes, felt unruly wind in their coiffures. They did not know what to make of it all. This so-called silence was deeply unsettling. More unsettling still is Cage’s assertion in a book he titled Silence: “There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear. In fact, try as we may to make a silence, we cannot.” He was fond of repeating a story about his experience in an anechoic chamber, a room designed to be utterly soundproof. This happened a few years prior to his composing 4′33″. “In that silent room,” the story goes, “I heard two sounds, one high and one low. Afterward I asked the engineer in charge why, if the room was so silent, I had heard two sounds. He said, ‘Describe them.’ I did. He said, ‘The high one was your nervous system in operation. The low one was your blood in circulation.” From this Cage concluded that all sound is music and the music is continuous. Only the listening is intermittent.

Nowadays we might wonder: Why all the fuss? Why get so upset over a little silence? Cage accounted for it by saying the audience had “missed the point. There’s no such thing as silence. What they thought was silence in 4′33″—because they didn’t know how to listen—was full of accidental sounds.” Audience expectations had been thwarted. Instead of chamber music, they were presented with the music of the world, breaking upon them from both inside and outside the concert hall. They heard coughs instead of notes, felt unruly wind in their coiffures. They did not know what to make of it all. This so-called silence was deeply unsettling. More unsettling still is Cage’s assertion in a book he titled Silence: “There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear. In fact, try as we may to make a silence, we cannot.” He was fond of repeating a story about his experience in an anechoic chamber, a room designed to be utterly soundproof. This happened a few years prior to his composing 4′33″. “In that silent room,” the story goes, “I heard two sounds, one high and one low. Afterward I asked the engineer in charge why, if the room was so silent, I had heard two sounds. He said, ‘Describe them.’ I did. He said, ‘The high one was your nervous system in operation. The low one was your blood in circulation.” From this Cage concluded that all sound is music and the music is continuous. Only the listening is intermittent.

And what more fitting place could be imagined for the debut of Cage’s “silent piece” than the Catskill Mountains? After all, this is the Land of Rip Van Winkle. Somewhere—it could be anywhere—in these fabled recesses, the affable Dutchman took that fateful sip from the “wicked flagon” and fell into a deep sleep lasting for twenty years. What did he dream about? No record of it survives, but it’s no stretch to envision old Rip’s dreamlife taking place in one or more of those spectacular landscapes later captured on canvases by artists such as Thomas Cole, Frederic Church, Ralph Blakelock, and Fred De Sawal. In his twenty-year dream, perhaps Rip soared like the Catskill eagle depicted by Herman Melville, which “in some souls can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces.” And who knows, maybe Rip’s sleep was so deep he did no dreaming at all, and instead listened over and over and over yet again to the music—the ferocious emptiness of it—that John Cage would one day capture in his silent piece we know as 4′33″. No doubt, stranger things happen in these mountains.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on November 9, 2018