When Circumstances Are Right

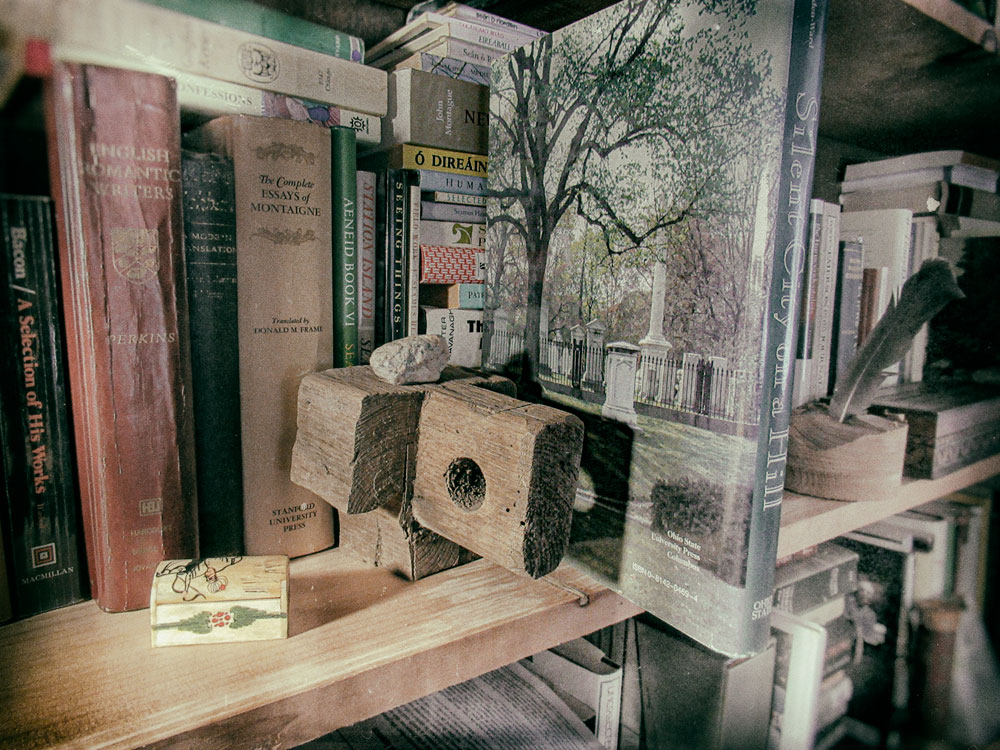

My study is dusty and cluttered, a room jammed with all the items that go with being O’Grady: books lining the walls and stacked on the floor, file drawers crammed with manuscripts, storage boxes packed with yellowed letters. Yes, letters. They date from the days when friends would write them to each other. I can’t remember the last time I received an actual letter in the mail. It’s just as well. I have enough stuff. “I am myself and my circumstances” says the philosopher. And “circumstances” is just a fancy word for stuff. I need to get rid of some stuff.

My study is dusty and cluttered, a room jammed with all the items that go with being O’Grady: books lining the walls and stacked on the floor, file drawers crammed with manuscripts, storage boxes packed with yellowed letters. Yes, letters. They date from the days when friends would write them to each other. I can’t remember the last time I received an actual letter in the mail. It’s just as well. I have enough stuff. “I am myself and my circumstances” says the philosopher. And “circumstances” is just a fancy word for stuff. I need to get rid of some stuff.

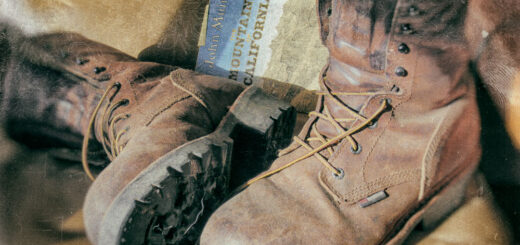

On top of one of my bookcases is a large Jeffrey pine cone, a gentle reminder of days spent on the East Side of California’s Sierra Nevada. On my desk is a granite rock I plucked from the waters of Walden Pond when I was in college. I used to have two Walden rocks, but at some point in the 1990s I became possessed of the idea to take one of those rocks with me on a climb to the top of Mount Shasta, a 14,180 foot dormant volcano clad with glaciers. Just below the summit is a boiling, sulfurous hot spring. I tossed the Walden rock into that cauldron.

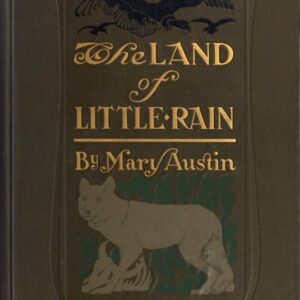

Perhaps the most peculiar item among the circumstances of my study is a tiny ivory chest containing the bones of a writer named Mary Austin. Well, not really her bones, just a few fragments of her cremated remains. I came upon them many years ago on a mountaintop in New Mexico, where they lay ignominiously scattered among the baloney sandwich ruins of a half century of hiker picnics. Mountaintops often prove to be weird places, attracting more than their fair share of prophets, peak-baggers, paragliders, and litterbugs. No surprise then that many a summit serves as somebody’s final resting place, though not necessarily by choice.

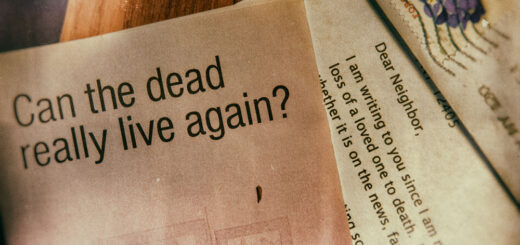

Mary Hunter Austin was born in Illinois in 1867 and died in Santa Fe in 1934. She is remembered today for her first book, The Land of Little Rain. It’s a pretty good read. She was a pretty good writer. Literary scholars have written innumerable things about her. I’ve written a few myself, including the story of how her remains wound up on the summit of an 8,500-foot peak outside of Santa Fe and then were forgotten. That story would be funny if it weren’t so sad. It was published years ago in a little-known literary journal. I forget the name of it.

Anyway, I thought I was done writing about Mary Austin—it’s been many years—but here I go again. Coming across cremated remains among the circumstances of one’s study is a powerful prompt. I tried to resist because I’ve been told I write too much about graveyards. Well, now you know why: my study has been serving as a de facto boneyard for almost thirty years.

Speaking of coffins, the few bits of Mary Austin’s remains in my possession have been kept respectfully in that tiny ivory chest. A friend gave it to me when she discovered what I had been keeping in a vintage Catskill Game Farm ashtray. “You’ve got Mary Austin in an ashtray?! What’s the matter with you?” As a poet she was not impressed with my literalism. She returned the next day with the tiny ivory chest and said it was for Mary Austin. For the last few decades, the author’s ashes have been housed there.

I had forgotten all this till the other day when I was tidying up and came across the ivory chest at the back of a file drawer full of my abandoned manuscripts. I don’t know how the tiny ivory chest ended up in such a spot. I must have put it there years ago because, frankly, who wants to be looking at a little coffin all the time? As soon as I saw it, I remembered a promise I made to myself when I gathered up those bits of bone from the trampled ground of a popular hiking destination.

There was no marker on that mountaintop, no sign that this was the grave of a writer who was famous enough in her day. The still air of that mountain peak on that warm September afternoon was redolent of urine. I’ve always wondered why the first thing people do when they reach a mountaintop is to relieve themselves. It just isn’t right. It’s even less right when the mountaintop is also a gravesite.

I picked up the few bone fragments I could see, put them in a plastic sandwich bag, and took them home with me. I swore at the time I would one day return to this mountaintop with Mary Austin’s remains and give them a proper interment—which is more than they received from the hired cowboys who unceremoniously deposited them there in 1939 when the mortuary that had been storing them went out of business. Nobody else wanted Mary Austin’s ashes.

At this stage in my life, it’s unlikely I’ll ever return to Santa Fe. That leaves me to wonder how I can fulfill my promise to reinter the remains. I don’t think Mary Austin ever visited the Catskill Mountains, but maybe she would enjoy the long view from one of our modest elevations, say, Hunter Mountain or Pratt Rock or Mount Utsayantha. Even better might be to take her ashes to Concord, Massachusetts, and spread them upon the waters of Walden Pond. I’ll have to reflect on this some more, but in the end, when circumstances are right, I will fulfill my promise.

©John P. O’Grady

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on December 23, 2020