Dreams of Virginia Dare

I was there the night it all began, but the greater part of this story I’ve had to piece together over the years from reports of others, mostly friends of mine, who are usually pretty honest. It’s customary in these situations to start by saying something like “Verily, this tale is true.” At least that’s how all the old books begin. They claim that the power of enchantment—whether it be a magical charm, or an eloquent poem, or a good story told around the table—is so great that it is able to overwhelm all of nature. I don’t know about that, but just try saying “I love you” to someone for the first time and see how the world is changed, for good or ill.

I was there the night it all began, but the greater part of this story I’ve had to piece together over the years from reports of others, mostly friends of mine, who are usually pretty honest. It’s customary in these situations to start by saying something like “Verily, this tale is true.” At least that’s how all the old books begin. They claim that the power of enchantment—whether it be a magical charm, or an eloquent poem, or a good story told around the table—is so great that it is able to overwhelm all of nature. I don’t know about that, but just try saying “I love you” to someone for the first time and see how the world is changed, for good or ill.

Nostalgia too must be something like this. After a couple of decades, people look back on their college years and say, “That was a magical time.” Those folks are speaking figuratively and from a distance. What I’m trying to do is figure out some things, and thereby draw a little closer to the offbeat phenomena of the world, which, if they aren’t magic in a literal sense are without a doubt “wicked,” as they say in Maine, “wicked weird.”

It was a college bull session. First day back for the fall semester and everybody was excited because there was a big football game the next day to kick off the new school year. A bunch of people were sitting around in the dorm lounge introducing themselves to each other or catching up on the summer’s news with old friends. Among them was a new guy named Leo LaChance, a freshman, who was on the cross country team. Talk got around to the courses people were taking and a couple said they were enrolled in Early American History. So Barb Taylor asked, “Does anybody remember Virginia Dare? I just love that name.”

Virginia Dare, you may recall, was the first child born of English parents in the new world: August 18, 1587, on Roanoke Island in North Carolina. Not a good place to be from, all things considered, since not long after her birth everybody there disappeared without a trace. A few years later, when a long delayed supply ship finally showed up from England, all they found were abandoned buildings overgrown with vines and a single word carved into a tree: “Croatoan.” Nobody knew what it meant and there were no further signs of what happened to those unfortunate souls. All of them, including the baby Virginia Dare, were gone, never to be heard from again.

We were in Maine, so North Carolina seemed a pretty exotic topic—warm weather, sunny beaches, spring breaks—and it gave rise that evening to all kinds of fantastic speculations and associations. Somebody said that he knew of a bar called Croatoan—he thought that was the name—but it was down in South Boston. Somebody else said he was going to start a rock band and call it Croatoan. He imagined that none of the members in this band would ever take the stage and nobody would know what they look like; instead they’d play in some hidden location far removed from the audience and pipe in the music via speakers so it would all be very mysterious and rumors could start that the band was really led by Jim Morrison, who hadn’t died after all.

That’s when Leo LaChance spoke up. He wasn’t called “The Bugman” yet. It was the first time anybody there had heard from him, so he was given the floor, and he surprised us by going on at length. Not a person in the room could have anticipated the succession of events after that. I realize that those of you who were there at the University of Maine will remember some of the incidents I’m about to recall—especially the infamous “Witch Hunt”—but so far as I know, the strange and disparate occurrences of those days have never been brought together in an adequate account. I don’t make any great claims for my own story, but it must suffice until a more satisfactory version is put forth.

Anyway, Leo LaChance launched into his story, telling the group—all of whom were strangers to him—that he had once been to Roanoke Island and had seen there a marble statue of Virginia Dare. It was sculpted in the nineteenth century by Maria Louise Lander, a friend of Nathaniel Hawthorne, and it was the most exquisite work of art he had ever seen. This statue was life sized, presenting Virginia Dare as a beautiful young woman, mostly naked, a detail Leo delivered with great relish. He described her as standing, scantily clad, in the midst of a fancy garden, with flowering trees and sweet-smelling shrubs all around. It was as if the baby Virginia Dare had somehow escaped from the ill-fated colony and had grown up and was now living in Eden or Arcadia or maybe, as Leo believed, Croatoan.

Anyway, Leo LaChance launched into his story, telling the group—all of whom were strangers to him—that he had once been to Roanoke Island and had seen there a marble statue of Virginia Dare. It was sculpted in the nineteenth century by Maria Louise Lander, a friend of Nathaniel Hawthorne, and it was the most exquisite work of art he had ever seen. This statue was life sized, presenting Virginia Dare as a beautiful young woman, mostly naked, a detail Leo delivered with great relish. He described her as standing, scantily clad, in the midst of a fancy garden, with flowering trees and sweet-smelling shrubs all around. It was as if the baby Virginia Dare had somehow escaped from the ill-fated colony and had grown up and was now living in Eden or Arcadia or maybe, as Leo believed, Croatoan.

Then he spoke of a legend concerning this statue, how on certain nights of the year it comes to life and starts walking around. “If only it were so,” Leo sighed. “Something like that is very hard to believe, I know, and I don’t go for it myself, but she does come to me in my special dream.”

That got a few snickers from the audience, but we all wanted to hear more about this special dream, so we encouraged him to continue.

“I’m at home and for some reason my family has this huge dead bear in the middle of the living room. It’s stuffed like it came from the taxidermist, so I ask around but nobody can tell me why this bear is here. ‘Who killed it?’ I keep asking my father, but he just tells me to go ask my mother, but I can’t find her anywhere. Next thing you know, a big tree starts growing out of the bear’s head. It’s huge and already very old, even though it just sprouted. As it rises up, I think it’s going to break through the roof of the house, but when I look up, there is no roof—it’s gone and everything’s just night sky with stars blazing and the tree soaring up there so high it looks like its leaves are the stars. Then way up there I see a woman swinging on a swing. She’s naked and her skin is shiny white like marble. It’s Virginia Dare. But she’s not a statue anymore, she’s alive and she’s swinging and smiling and waving down to me. She wants me to climb up the tree but the trunk is so big I can’t get my arms around it. There’s no place to grab hold. I get all upset because I can’t climb the tree and I won’t be able to go up there and sit on the swing and swing back and forth among the starry leaves with Virginia Dare. It’s really frustrating. But she keeps swinging and smiling and waving down, as if to urge me on, so I try once more. Then I wake up.”

He finished his recitation by expressing the wistful hope that one day, if that statue of Virginia Dare really does come to life and go for walks, she might make the trip up to Maine and pay him a visit. “In the meantime,” he concluded, “at least I have my special dream.”

A couple of the women in the audience thought the story quite romantic, but mostly people just snickered some more and exchanged knowing looks or the cuckoo sign with each other. When some of the guys started teasing him about being in love with a chunk of rock, Leo just got up and left, insulted.

But the talking went on well into the night, moving away from Leo and his statue to related topics of magic potions and amulets. “Wouldn’t it be fun,” Westphal suggested, “to find some way to grant Leo his wish and have that statue stop by and give him a thrill?” More plotting and scheming followed. At last somebody—I think it was Crilly Fritz (a real name by the way)—said: “Let’s go find the Magician!”

The Magician was the nickname of a guy whose real name was Forrest Woodroe, an otherwise lackluster accounting major save for one curious fact: he came from a part of Maine which, at the time we’re talking about, still had a vibrant folk tradition of magic. It was somewhere up near Solon or Carrabassett maybe. The joke around campus was that while other kids were growing up playing with dolls or chemistry sets, the Magician was concocting potions and working out incantations. The bookshelves in his dorm room were lined with volumes by Albert the Great, Cornelius Agrippa, and Giordano Bruno. Forrest regularly wrote cryptic letters to the college newspaper interpreting current events in light of the prophecies of Nostradamus, signing his bizarre messages with the penname Nick Cusa. Guys like this show up every fall on college campuses all across America. What separated Forrest Woodroe, what kept him from being just another freshman goofball, was the fact that people actually witnessed him alter the course of the 1975 World Series. It happened the year before I got there, but here’s what they say about it.

Going into the Sixth Game of the Series, the Red Sox are down three games to two against the Reds, playing at home in Fenway. Everybody in New England is barnacled to their TV screen. The game goes into extra innings. Now it’s past midnight. Bottom of the twelfth and leading off for the Sox is Carlton Fisk. On Pat Darcy’s second pitch—a low inside sinker—Fisk takes a mighty swipe. The ball goes soaring up in a meteoric arc toward the wall in left field. It’s a crisis, a moment when the past has least hold on the present and the present has greatest hold on the future. The ball becomes a lifeboat with all of New England’s hopes crammed into it, and it’s drifting dangerously toward the foul line.

Fisk takes a tentative step down the line toward first; stops; watches. Time stops and watches too. That’s when the guys watching the game in the dorm lounge notice Forrest is standing performing this strange rhythmic motion with his arms, waving to the right as if to urge the lifeboat to keep from running afoul. Each wave is joined with a hop, so he’s waving as he’s bouncing his way across the room. Everybody’s seized with wonder looking at Forrest, when suddenly a loud “Hey, look!” rings out in the room. Eyes return to the TV screen, where Carlton Fisk is now doing the exact same thing as Forrest—waving his arms as he hops, in just the same fashion, even keeping exactly in sync. Three waves with three hops: whoosh, whoosh, whoosh. It is a very strange moment and it’s going on even still: Forrest Woodroe leading Carlton Fisk in this weird dance across two hundred and fifty miles and all of eternity.

But everything changes when the lifeboat hits the yellow foul pole above the wall—“Fair ball!”—and becomes a game-winning home run. The day is saved and Carlton Fisk is a hero! And to those sitting in the lounge of York Hall at the University of Maine on this faraway October night, so is Forrest Woodroe.

Even though the Red Sox would go on the next day to drop the ball and lose the Series to the Reds, that Sixth Game—capped by Fisk’s unforgettable performance—went down as the greatest in World Series history. And Forrest Woodroe, for his part, stepped into campus history and was known ever after as the Magician.

As for what went wrong with the Sox in that remaining game, the Magician had a role in that too. Much to everybody’s dismay, he was unable to make it back from some unspecified business in time for the game. The guys were counting on his working the magic one more time. They were plenty mad when he didn’t show. Somebody even suggested that they burn the Magician at the stake for his failure, but death threats are ordinary in the mouths of disappointed Red Sox fans. Just ask Bob Stanley.

Cooler heads, though, prevailed that night in Maine, especially once it was reasoned that if this guy can sway the course of a World Series game, there’s no telling what he might do to anybody who tried to mess with him. No one was willing to take that chance. Indeed, there are those who say that the Magician was so indignant about even the mild rudeness he suffered from those Red Sox fans when he finally did show up, that he put a hex on their team so they would never win another World Series. One can only conclude that this, combined with the Babe Ruth curse, adds up to some pretty potent hoodoo.

And so the Magician now enters this story about Leo LaChance and the statue of Virginia Dare. I myself have no part in the rest of it, save for the gathering of details after the fact. I have to admit that I did play a small role in hatching the scheme that called for the Magician’s services, and it was me who came up with the idea to carve “Croatoan” into the Hollow Tree, thinking it might work as a kind of navigation beacon for Virginia Dare—but I didn’t think anybody would take it seriously. Come on, this was a bull session.

When those guys from the dorm lounge—including, among others, Crilly Fritz, Peter Snell, and a muscle-bound guy that everybody called “Animal”—went off looking for the Magician, I stayed behind and so did Westphal. For a little while we sat around trying to impress the women by making fun of how gullible those nitwits were. But then I got tired and went off to bed, leaving Westphal still trying to impress the women.

What went down next at the Hollow Tree came to light just this past Christmas—Westphal filled me in. Turns out the Magician was perfectly willing to help those guys help Leo get his girl. Carving the word Croatoan into the Hollow Tree was a great idea, the Magician said, but to cast an effective love charm—especially if it involved animating a marble statue—that would require a more formal ritual, for which the presence of all these guys was required. They eagerly agreed to it.

So it must have been at that point the Magician went to his closet, grabbed the blue denim laundry bag and shook out a bunch of dirty clothes onto the floor. Then he gathered a few items from a drawer, stashed them into the bag in a big clatter, and the whole crew set off for the Hollow Tree.

The Hollow Tree was a beloved campus landmark, a huge old cottonwood on the long, sloping lawn above the Penobscot River. It was the biggest tree around, and some people even claimed it was the largest in the State of Maine. At the base of its immense trunk was a gaping hole, wide as a church door, which led into an immense, rotted-out interior. Inside was cozy as a chapel, with space vaulting upward into the dim rafters of the world, where statues of angels and Madonnas might lurk unseen in dark niches. There was room enough in there you could celebrate a mass if you wanted, or have a party, or—more intimately—bring a date and make out.

Most everybody who attended the university in those days sooner or later did. It was a rite of passage and widely held that if you didn’t make out in the Hollow Tree at least once before graduation, you couldn’t really call yourself a University of Maine alum. Over the decades, the aura of all those comings together inside the tree must have inhered into the very xylem and phloem of that venerable monarch; if tree rings were a record of lovers’ trysts rather than years, then this cottonwood easily qualified as the oldest living thing on earth.

I like to imagine that when the Magician and his band of dorm rats showed up there in the wee hours of the night, a pair of terrified lovebirds were flushed from cover, bolting out from the Hollow Tree as the truth sometimes does in the course of things. There they go, a couple of quail, bobbing as they weave, hopping and tripping as they tug up on jeans, open shirt and open blouse unfurling behind them in a ghostly flutter. They flee across the dark lawn toward still darker reaches in the distance, until their fantastic forms fade into the same stuff from which everything after midnight is made, two blurs in the blur of darkness.

The Magician and company now stood in front of the Hollow Tree. Preparations were made for the ritual. The Magician emptied out the clattering contents of the blue denim bag: a can of Sterno, a camping pot, a potholder, some matches, and another item, hard to see. The Magician instructed Crilly Fritz to go inside the tree and carve Croatoan somewhere in its heart. With gusto Crilly pulled out his pocketknife and vanished into the cottonwood.

By the time he emerged from his task, the Magician had things set up on the grass. The can of Sterno was going. The guys stood in a semi-circle around him. Using the potholder, the Magician suspended the camping pot over the blue flame. He had begun his conjuring. I guess you could call it that.

All of the guys now went dropped-jawed, looking back and forth between what the Magician was doing and one another, or maybe they were just looking for the exit sign. The Magician’s spell, performed in a tone of voice that seemed to rise directly out of a catacomb, went something like this:

“Draw Virginia from the wild,

Home, my song, draw Virginia home,

Home to Leo, home, my song, and pray:

These words I weave as Venus bands

Will draw, draw Virginia home!”

Most people are discomfited by poetry in one way or another, and these guys were no exception. But they were thoroughly undone when the Magician started to lower into the camp pot a waxen figure—some say it was in the shape of an angel, others say it was a bear, and there is one report that insists it was just a handful of birthday candles—and proceeded with his incantation:

“Draw Virginia from the wild,

Home, my song, draw Virginia home.

As Croatoan takes its hold

Deep in the heart of this tree,

Draw Virginia home, my song,

Draw Virginia home.

As this wax melts in one

And the selfsame fire,

Even so let Virginia melt,

Melt with love for Leo–

And to others’ love let loose all hold

And draw Virginia home!”

By no academic standard can this be called good verse. You won’t find stuff like this in a Norton Anthology. But if a poem is measured by the effect it has in the world, then this one reversed the magnetic pole of reality.

First thing the guys hear after the Magician finishes is the growling. It erupts from somewhere deep inside the tree, then pounces out like a panther or a really mad Bigfoot. Everybody, including the Magician, goes lime white and starts trembling like an aspen grove. The Magician himself is the first one to break, taking off like a barn-sour rental horse. The rest of them are right on his tail.

Given what happened over the next few days, it’s no wonder these guys fell into tacit agreement never to mention this episode again. The whole thing is embarrassing. Even today if you manage to track one of them down and ask about that night around the Hollow Tree and how it might have been connected to the “witch hunt” that followed, they will deny any knowledge of the topic. It’s the main reason the story didn’t get out before this.

Here’s the next part.

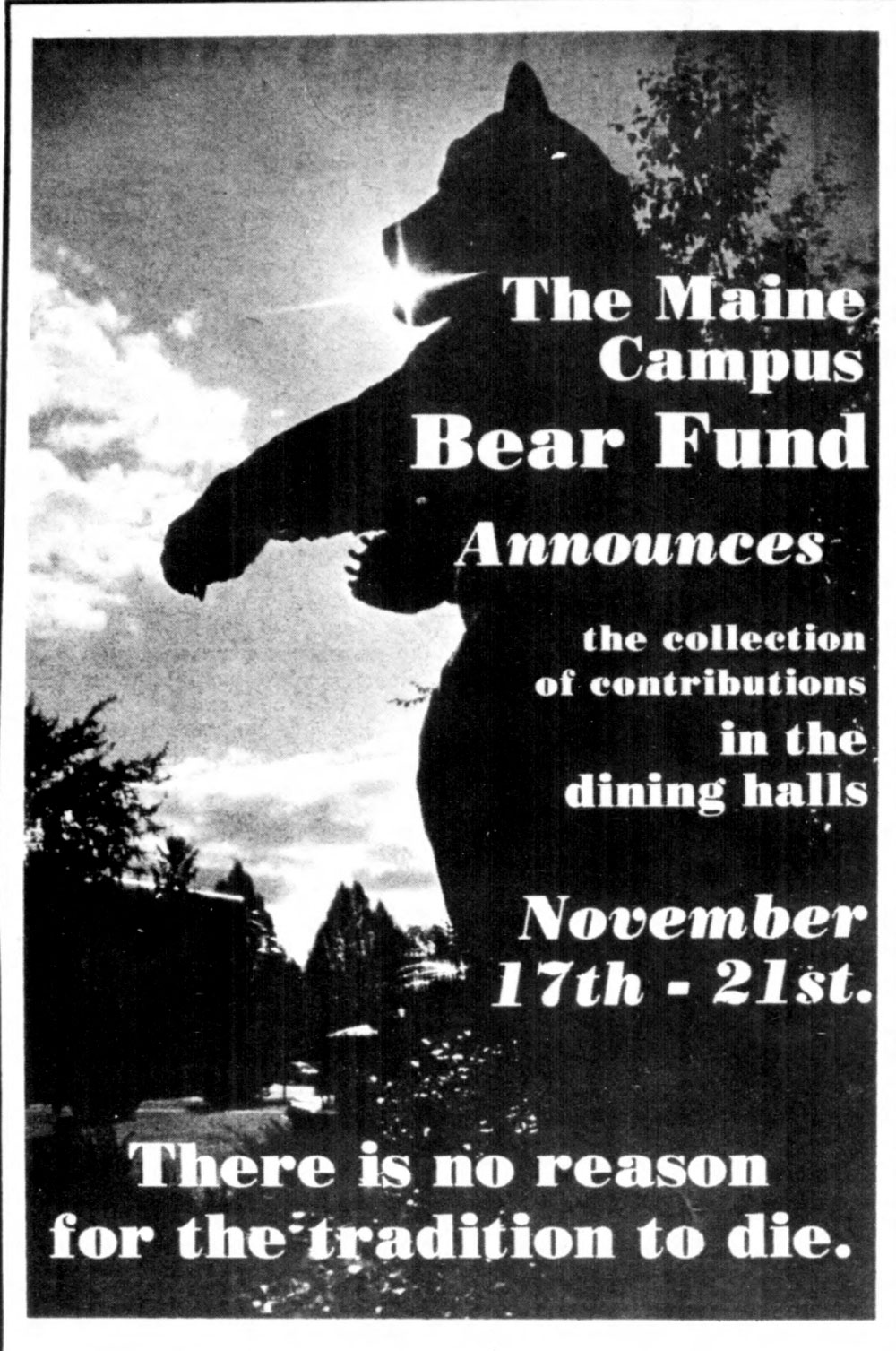

The other famous campus landmark was in front of the gym: a bigger-than-life size statue of a black bear. The black bear is the University of Maine mascot and this one had been around since the days of Rudy Vallee. I’ve seen a yellowed photo of old Rudy standing next to this bear. The singer is wearing a long raccoon coat and is crooning something through megaphone, probably the “Maine Stein Song.” So this picture would have to have been taken in the late twenties. Otherwise pretty ferocious looking, the bear was made out of wood and plaster, so by the time we got to college in the seventies he had been chewed up by termites and was looking pretty mangy.

On the very next morning after the high jinks around the Hollow Tree, Peter Snell was heading to the gym when he was shocked to discover the bear was gone! There was the empty pedestal, and all around it he could see footprints and deep ruts leading off in the direction of the woods. Peter Snell had flunked basic math a couple times, but this two-and-two he could put together. He ran back to the dorm terror stricken, with the whole pack of junkyard dogs that was his imagination nipping at his heels.

He found the rest of the Magician’s assistants from the night before and warned them of the big trouble afoot. Whatever level-headedness had remained among them had now been dropped into a vat of acid. Greg Downing, another dorm resident, happened to be walking past the room where they were in heated deliberation. What he overheard didn’t make much sense, so he thought it was just another bunch of Saturday morning drunks. He wasn’t able to say who said what, but among the fragments of conversation preserved in his report are these:

“Shit! Do you really think that bear’s name was Croatoan?”

“Shit! Is that what we heard growling in the tree?”

“Shit, we gotta get that bear back—the football team’s gonna kill us!”

And lastly: “That Magician is a dead man!”

Then the guys charged out of the room—no need to repeat their names, you know them by now—and went off, presumably to grab the Magician and force him to set matters aright. One of the things we learned in political science class was that the solution to the problems of democracy is more democracy; the same might be said, at least in this case, when it comes to folly.

Now, believing that a ratty old statue of a bear, some dilapidated university mascot, could be conjured—even by mistake—into life, and that its name would just happen to be Croatoan, is by no means as far fetched as you may think. Wacky behavior stemming from wayward belief happens all the time in America. It may be the only story we’ve got.

Compare, for instance, the man from Plymouth, Massachusetts, who, a couple hundred years ago, had an idea about how to bring in a few more tourist dollars to his pretty how town. He went down to the harbor and walked out onto the strand of dreams. Or maybe it was a mudflat. The place was strewn with unremarkable boulders dropped there about ten thousand years ago—a heap of junk a glacier didn’t want anymore. It had been lying there like this for millennia. But he walked around for a while, like people do in Fairly Reliable Bob’s Used Car Lot, and at last selected a boulder, perhaps the least remarkable of them all, into which he chiseled four numerals: “1620.” Next thing you know, the rock exploded into myth.

Historians assure us that the picture of Pilgrims stepping off the Mayflower onto this rock as if it were a welcome mat to the new world is little more than a charming bit of Thanksgiving lore, but it nevertheless translates into some overly firm belief. In 1835 Alexis de Tocqueville (that shrewd Frenchman) observed just how obsessed Americans had already become with this coffin-sized piece of glacier-trash: “I have seen fragments of this rock carefully preserved in several American cities, where they are venerated and tiny pieces distributed far and wide.” Today Plymouth Rock is housed in a kind of Greek temple, and it draws millions of people a year to an otherwise unexceptional place surrounded by sour cranberry bogs, lonesome pine woods, and smelly salt marshes. Talk about conjuring!

Well, the guys did find the Magician that day, sometime around sunset, and hauled him back to the Hollow Tree, where they planned to make him cancel the faulty spell cast the night before. But when they got there a lot of angry people were swarming about on campus—the football team had just lost—and the Hollow Tree was in plain sight, so our boys beat a hasty detour to the forest behind the university and went down the woods path that the cross-country team trained on.

At some point they left the trail and pushed into the dark spruce and fir forest where they found hundreds of small cheesecloth bags festooned from nearly every branch of the evergreens. The guys thought this a little strange but they had bigger and stranger worries: they had to get that bear back before somebody got hurt—namely them—at the hands of a superstitious football team and its angry fans.

By the time they reached a spot secluded enough to perform whatever crazy ritual deemed proper by the Magician, dusk had settled in.

“Get going,” Animal said as he gave the Magician a nasty shove, “get that bear to go back where it belongs.”

“Look,” the Magician said, “I’m not sure I can. I don’t know any spells that work on bears.”

“What do you mean? Look what happened last night. Sure as hell looked like it worked to me. Just say the same thing, and make sure you mention the bear’s name again.”

“What are you talking about? What name?”

“Croatoan, you idiot!”

“I don’t have my magic kit,” the Magician said, “I left it at that tree last night. When I went back this morning to get it, all the stuff was gone.”

“We don’t have time for that crap. This is serious. Look, here’s some candles. We’ll light them and stand around holding them and you just sing that damn bear back to where the hell it goes. Now do it!”

Alas the Magician, wanting his bag of tricks, did the only thing any performer can do in such a situation—he winged it. Who knows exactly what words he chanted, but they came through in that same catacomb tone, only now they tumbled along through the dusky forest like empty trashcans in a Halloween wind.

Little is understood anymore about the relation between word and world. In sounding it out, you might think there is some vast separation between them, starting with the letter “L” and reaching out to every level of meaning. But this would be an error. There is no separation, or so they say. To the artists who work in this medium—which goes by the name of magic—there is a conviction that nothing happens by chance or luck. These people align their actions with some bigger principle, in some cases bright and shining, and in others very dark indeed. All of them use the human voice to express the inner nature of the mind, to draw forth its secret manifestations and to declare the will of the speaker or a guardian angel or whatever demon might have stowed away for the course of any particular human life.

Maybe, as you say, all of this is just a load of hooey. You wouldn’t be wrong. But if it had been you jogging down the woods path that evening on your way back to the fieldhouse after a strenuous and solitary training run because you showed up late for cross country practice, and you heard that creepy chanting coming from the dark woods and had seen the candlelight flickering among the somber spruce and fir boughs, then maybe you would have been struck as poor Leo LaChance was struck that evening: with the firm impression that there was a coven of witches out there in the University Forest and they were conducting some dark ritual, probably a black mass.

“Holy shit!” you would say picking up the pace and running the fastest mile you’d ever run in your whole life (and nobody there to see), just so you can get back to campus in time and sound the alarm: “There’s witches out there—I mean it—and they’re doing animal sacrifices and who knows what all! We gotta stop it!”

Yes, had all this actually happened to you, then a few pages in the underground history of the University of Maine would have been devoted to your exploits. That is, if anybody bothered to write it.

But this is Leo’s story and here’s what happened to him.

He emerged from the forest and Paul-Revered it around campus, hustling from dorm to dorm shouting about witches. At first people just dismissed Leo as a rowdy or a drunk, but then he managed to convince a couple of Resident Assistants at the dorm to go into the woods with him to investigate.

Flashlights in hand, they retraced Leo’s path. Along the way, they saw the cheesecloth bags hanging in the trees. Nobody knew what they meant, but agreed they looked pretty sinister, like little ghosts that had snagged themselves in the branches. Then they found some smoking candles lying in the forest duff. But what clinched it was when they heard, from deep in the recesses of the night woods, a horrible racket of breaking branches and snorting animals and demonic cursing, as if a bunch of people were running away. It sounded like a coven of witches!

There’s no telling where in the human mind that switch is that, if thrown, turns on mob mentality, but Leo, groping around in there for anything to throw some light on his experience, managed on that memorable Friday night to trip it.

The whole campus lit up in a frenzy. It was like a kindergarten game of Telephone gone haywire, or an adult game that politicians used to play called the Domino Effect. Whatever it was, it was nuts and it was fast. As Westphal describes it: “Next thing you know there’s two hundred guys with baseball bats and hockey sticks pouring out of the dorms and heading for the woods. God help anybody they found out there. I think they killed a couple of black cats, I’m not sure, but a lot of those guys were already drunk and pissed off that the football team had lost, so when they couldn’t find any witches, they started beating each other up. That witch hunt was the scariest thing I’ve ever seen, and it went on all weekend.”

It was as though the campus had sent up a weather balloon into Cloud Cuckoo-land. It stayed up there for a day and a half. In the meantime, the Witch Hunt was big news and almost everybody was taking it seriously.

Since Leo was the first one to spot the trouble, he became a hero of sorts, as well as the de facto spokesman for what was going on. He was now the Cotton Mather of U Maine, demanding the purge of baneful influences. He thought people would be interested in what he had to say, so he set up a sort of press room in the dorm lounge.

At first it was just a single reporter from the campus newspaper, but as the scope of the events widened, press from off campus started showing up. In eastern Maine, any fuss is big news. Soon there were rumors that TV cameras were on their way and maybe Huntley and Brinkley too. Lucky for Leo, those who knew the real story, including the fine points of his special dream, had their own problems and were lying low.

With Leo at the helm, all kinds of fools started making report. Stories came in about strange mounds of earth discovered out in the forest. “It must be where the witches buried their victims,” exclaimed one sociology major on Sunday morning. For the rest of the day you saw guys heading off into the woods with shovels. Then came the psychology major who said he saw a bunch of naked people, obviously witches, darting among the trees. “And if you don’t believe it, here’s a shirt I found out there!” This sent even more people out into the woods; nobody wanted to miss out on a chance to lay hands on these witches. Finally, there were several UFO sightings that weekend, and one thoroughly besotted philosophy major claimed to have been abducted by the aliens, vicious beings who—he insisted—had robbed him of everything. “I can’t even remember my name,” he sobbed over and over to the reporters, as Leo stood there with a comforting arm around the poor scholar’s shoulders. “We must recover this good man’s name,” Leo intoned for the record.

Monday morning was when that weather balloon came crashing down. It dropped in the form of a graduate student in forest entomology who came bursting into Leo’s “press room” with a bug up his ass. He said he had been away for the weekend and just gotten back. He had this big experiment going for his dissertation research on spruce budworm. It involved setting up cheesecloth traps out in the forest to catch the insects. When he went out to the site this morning, he found all the traps had been ripped from the trees. Three years of research down the drain. Or up in smoke as the case may be, because he learned that students from one of the Christian organizations had pulled them down and burned them in a ritual bonfire out in the forestry school’s “Stump Dump.”

“They thought my traps had something to do with witchcraft!” the bewildered grad student declared, as reporters busily scribbled down notes. He also said something about finding a badly charred bear’s head nearby. “What the hell’s going on around here?” he demanded.

“Oh shit,” said Leo, as he bolted out of there before the grad student could grab him or any TV cameras showed up.

Next day the campus newspaper headline read: “Witch Hunt Proves A Witch Hunt. Campus Bugged By False Report.” Many humiliating details found their way into that story, but somehow Leo was spared public exposure of his special dream. At least he still had that. Also, there was no mention of the Magician, Crilly Fritz, Peter Snell, Animal, or any of those other mischief-makers from the dorm.

Even today very few know about Virginia Dare’s role in all this. For Leo’s sake, I’m glad. I hope he forgives me for invoking her one more time, but I think these things can now be laid to rest. Everybody should know that the Witch Hunt wasn’t really Leo’s fault; he was just caught up in a swirl of circumstances. Once that story broke, his reputation on campus was ruined. Nobody called him a hero after that. They didn’t even call him Leo anymore. Instead, he was simply “The Bugman.” And the Bugman he remains.

There’s a mawkish pleasure one takes in calling to mind events such as these. Sometimes I think my college years were misspent in pulling pranks and cutting classes so I could sit around and write stories like this to entertain my friends. Then I comfort myself by thinking that nothing that happened back there, no matter how silly, was far removed from anything else going on in the world. It was the seventies and everybody was doing this kind of thing. Call it the “spirit of the times.” Every age has one.

“What a waste!” people say when I tell them the kinds of things we did in those days. “How did you ever make anything of yourselves?” Well, maybe it’s like the millions of seeds a cottonwood tree flings out into the world each spring, those tiny, feathery parcels of hope that float together in the air for a while, just drifting around in companionable oblivion. Only one or two of them might ever come down to earth and find a nurturing spot to take root, someplace where they might indeed “make something of themselves.”

After all, while we were sitting around a University of Maine dorm on that Friday evening a quarter century ago, concocting schemes to animate a statue and put a love spell on it, at the same time on the other side of the continent, there were others with names like Jobs and Wozniak sitting around conjuring up a computer that would be named for a fruit that comes from a tree in Eden; a computer small enough and friendly enough that everybody in the world might own one, a magical box to be connected to millions of other boxes all over the world, so that in the end, no matter whatever else might be said of any individual, each would be a node in some infinite web, each an electric sparkle in the eye of Indra.

And thus my wayward college days are redeemed—because they were never lost in the first place, never removed from the center of things in this center-less universe. In fact, so far as this story goes, they are the center. It’s mind boggling to consider: whatever it is that causes one idea or name to gain purchase in the wider world while another fades away just may be what ultimately distinguishes a college prank from true magic. Or, as some are inclined to see it, history from myth.

In any case, you may be wondering how it came about that I should now have all these details. Perhaps you’re curious as to what happened to the people who appeared in this sketch, or maybe you’d just like to check out these places for yourself, much as literary tourists do when they rummage around the Catskill Mountains looking for Rip Van Winkle’s bed, or when they scour Wall Street trying to find the building Bartleby worked in. There’s no going back to such places, except by the way we just came. But if you insist on historical accuracy, I’ll do my best, though this particular bag of tricks is nearly empty.

First of all, the Magician. He did graduate from U Maine and went on to Harvard Law School. After that he got a job with some Big Eight accounting firm and got busted in the eighties for insider trading. Last I heard he’s selling furniture in Farmington, Maine. The rest of those guys from the dorm I haven’t seen or heard about in years, but with names like Crilly and Animal, you can be sure they are well known in their respective neighborhoods, wherever they may be. As for the Bugman, he dropped out of college after one semester, to chase his special dream elsewhere, maybe in Croatoan.

Speaking of Croatoan, for several years after these events, lovers and other visitors to the heart of the Hollow Tree were baffled by this odd word they found carved there. It became part of the campus folklore. There was even a story about a young couple who, not long after graduation, had a baby they named Croatoan, no doubt because she was conceived in the Hollow Tree.

Ah, the Hollow Tree. Sad to say, but even mythical giants must fall. Sometime after I left Maine, the Hollow Tree came down. I can only hope that it wasn’t rudely toppled as if it were just another piece of timber sliced up into logs and hauled off for target practice in the Stump Dump, where junior lumberjacks fling axes at old carved hearts and one mysterious word—or worse, carted away to the Old Town mill and pulped into the paper you’re reading this on. I would hate to think that this book is all that remains of a million “I love yous” and one special dream. Whatever, the Hollow Tree is gone from U Maine. I wonder if anybody there even remembers it anymore.

As for that old black bear mascot that disappeared—his name wasn’t Croatoan. As far as I can determine, he never had a name. Nor did he ever stand up from his pedestal and stalk the campus. Turns out that on the Friday evening before the disappointing football game, the Alumni Association had held a little ceremony. The old bear was being retired. The president of the university said some gold-watch words, then a crane hoisted the crumbling bear onto a flatbed truck that carried it away and unceremoniously dropped it off in the Stump Dump, for lack of a better paddock. Given the mayhem of the next few days, it’s not surprising that nobody ever asked about its mysterious disappearance from the Stump Dump. But there’s an aging entomology grad student—still trying to repair the damage to his career after the disastrous spruce budworm experiments—who could tell you a thing or two about that bear’s fate.

So if you had your heart set on seeing a bear at the University of Maine, don’t fret—they replaced it. The new mascot is a bit smaller—“leaner and meaner” as the Alumni Association likes to say—and it’s made of cast bronze. Some say bronze was chosen so as to prevent the rotted out destiny that overtook its predecessor. But there are a few—and you know their names—who believe that using heavy metal was the only way to ensure that if this mascot should ever come to life, its own weight would keep it from going anywhere. Thus this bear is now fixed in place more firmly than most treasured beliefs.

At long last, there is the mystery of the growl. As I said, I was only able to pick up the threads of this story thanks to Westphal. I paid him a visit over Christmas down on Mount Desert Island and we got to talking about our college days. The Witch Hunt came up, as it sometimes does when we get together. This time he provided all of the details of the events at the Hollow Tree and I wondered how he came upon this expanded version. I knew he hadn’t gone along with the Magician and company that fateful night. I pressed him.

“So what gives?”

“Come on down in the cellar with me.” He grinned impishly, an expression I know all too well.

Westphal lives in an old house. Cellars in these places are spooky. They’re dimly lit and smell like the earth’s dirty laundry. As he led me over to some dark shelves on a back wall, he said, “Hey, O’Grady—that growl? It was me. I beat those guys to the Hollow Tree and was hiding inside, up in one of those dark places you can’t see from below. I scared the shit out of them—you should have seen it.”

“No way!” I said.

“Well then, how do you explain this?” He reached up to the highest shelf and brought down an old blue denim bag, clattering with stuff inside. He handed it over to me. We were a couple of bank robbers and here was my share of the loot.

And that’s all I got.

©John P. O’Grady

©John P. O’Grady

This story originally appeared in Grave Goods: Essays of a Peculiar Nature by John P. O’Grady (University of Utah Press, 2001)