Walden in the Catskills

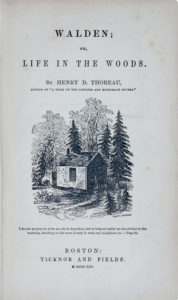

The writer Henry David Thoreau is famous for a hut he built with his own hands on the shore of Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts. To be more precise, he is famous for the book he wrote about his two-year residence in this hut. It was published in 1854 and bore the title: Walden; or Life in the Woods. The book was, for the most part, ignored during Thoreau’s lifetime, but it slowly gained recognition over the years. Today it stands as one of the monuments of American literature. Few realize that Thoreau’s “experiment in living” at Walden Pond began with a reminiscence of the Catskill Mountains.

On the first morning he awoke in his new home—July 5, 1845—Thoreau wrote in his journal: “Yesterday I came here to live. My house makes me think of some mountain houses I have seen, which seemed to have a fresher auroral atmosphere about them, as I fancy of the halls of Olympus. I lodged at the house of a saw-miller last summer, on the Caatskill Mountains, high up as Pine Orchard, in the blueberry and raspberry region, where the quiet and cleanliness and coolness seemed to be all one,—which had their ambrosial character.” The house Thoreau refers to was that of Ira Scribner and his wife Mary. It was located just a few hundred yards upstream from the precipice where Kaaterskill Falls makes its first grand leap. In July of 1844, when Thoreau and his friend Ellery Channing stayed there, Scribner was just putting the final touches on this new boarding house, which he called Glen Mary Cottage in honor of his wife. At that stage, the structure “was not plastered, only lathed, and the inner doors were not hung. The house seemed high-placed, airy, and perfumed, fit to entertain a travelling god. It was so high, indeed, that all the music, the broken strains, the waifs and accompaniments of tunes, that swept over the ridge of the Caatskills, passed through its aisles.” Not long after that, “Scribners’” would become the favorite haunt of Jervis McEntee and other Hudson River School painters, who could neither afford the steep rates of the nearby Catskill Mountain House nor suffer the hoity-toity air of the place. Like Henry Thoreau, they preferred the modest, Parnassian accommodations of Glen Mary Cottage.

Surprisingly, no direct mention of the Catskills is made in the final published version of Walden. As Alf Evers noted in his standard history of the region: “Thoreau cut all mention of the Catskills from his passage dealing with the sawmiller and his house.” As for the high-placed, airy boarding house Thoreau found so charming, the proprietors operated it for the next twenty-five years before selling it to Peter Schutt, owner of the nearby Laurel House. What happened to Glen Mary Cottage after that is lost to history. Just as it disappeared from the pages of Thoreau’s masterpiece, so too it disappeared from the landscape. According to Evers, whatever remnants of the house survived into the second half of the twentieth century were “bulldozed into oblivion, except for a part of its foundations, in order to make room for a parking lot for the New York State Conservation Department.” Other authorities, however, insist the bulldozers were not clearing the way for a parking lot but for a horse corral. In any case, no vestige of Glen Mary Cottage is to be found on the purported site it occupied.

Thoreau’s hut too disappeared from its landscape, though not quite as thoroughly. Significant traces of it remain. I myself am in possession of one—and the story that goes with it.

The provenance of Thoreau’s hut after he moved out in 1847 is well-established. He sold the structure to an Irishman living in the neighborhood, who proceeded to move it to a nearby beanfield. There he lived in it for a while. For reasons unknown, the Irishman soon abandoned the hut and it stood empty for a period of time, until a man by the name of James Clark—a self-proclaimed disciple of Thoreau—decided to buy it. The young man’s family owned a farm nearby and he arranged to have the hut moved onto one of the cow pastures there. Clark thought that living in Thoreau’s hut would provide him with some much-needed inspiration. Things didn’t quite work out that way. Apparently the solitude and spartan lifestyle played tricks with his head. He started going daft. As one local historian tells it: “Finally the poor fellow became insane and was placed in an asylum.” After that, the orphan hut was used to store grain. Then for a couple years a family of pigs occupied the structure without apparent incident. Finally, the Clark family barn being in need of repair, the hut was cannibalized for boards. At that point, Thoreau’s famed abode was incorporated into the barn and disappeared from history.

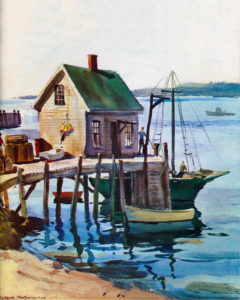

Until it returned in the late 1990s—on an island called Great Cranberry off the rocky coast of Maine. A wealthy family “from away” desired to put a lavish addition onto their already lavish summer home on the island. They hired my friend Westphal to do the job. He’s a builder. I happened to visit him during the time he was working on the project. He took me out to the site. This was in the dead of winter and the day was excruciatingly cold. The framing had just been completed, after an earlier setback in the fall. To warm up after touring the construction, we stood around a burn barrel roaring with a fire. Westphal was tossing in hunks of wood to feed the flames. “Hey,” I said, “that looks like really old wood. Where’d it come from?” He told me the story.

Until it returned in the late 1990s—on an island called Great Cranberry off the rocky coast of Maine. A wealthy family “from away” desired to put a lavish addition onto their already lavish summer home on the island. They hired my friend Westphal to do the job. He’s a builder. I happened to visit him during the time he was working on the project. He took me out to the site. This was in the dead of winter and the day was excruciatingly cold. The framing had just been completed, after an earlier setback in the fall. To warm up after touring the construction, we stood around a burn barrel roaring with a fire. Westphal was tossing in hunks of wood to feed the flames. “Hey,” I said, “that looks like really old wood. Where’d it come from?” He told me the story.

Turns out that barn on the Clark family farm in Concord had stood for many years after the incorporation of Thoreau’s hut. In the late 1980s the barn was finally dismantled and the reclaimed wood stored away until a buyer could be found. That buyer proved to be the fellow who wanted to put a lavish addition on his summer home on Great Cranberry Isle. The old barnwood was shipped to Maine. Westphal agreed to use the sketchy materials, despite his doubts about their integrity. It was pretty old wood and wasn’t going to support the load of the roof. Westphal explained this to the owner but was told to use the stuff anyway. So he did. Shortly after the last rickety timber was put into place, the main supporting beam gave way with a loud crack—and the whole shebang came crashing down. Oh well, time to start over with fresh lumber.

“What happened to all the old barnwood?” I asked Westphal. “And what about Thoreau’s hut?”

“What do you think, O’Grady? You’re holding a chunk of it right there in your hand. Now toss it into the barrel.”

I couldn’t do it. I just had to keep that old piece of wood. I took it home. As I changed residences over the years, that piece of wood has moved with me, here and there, to and fro across the continent. Now at last it’s back home, sitting on my bookshelf here in the Catskill Mountains, close by my copy of Walden and where it all began.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on January 4, 2019