The Refreshment Pavilion at Kaaterskill Falls

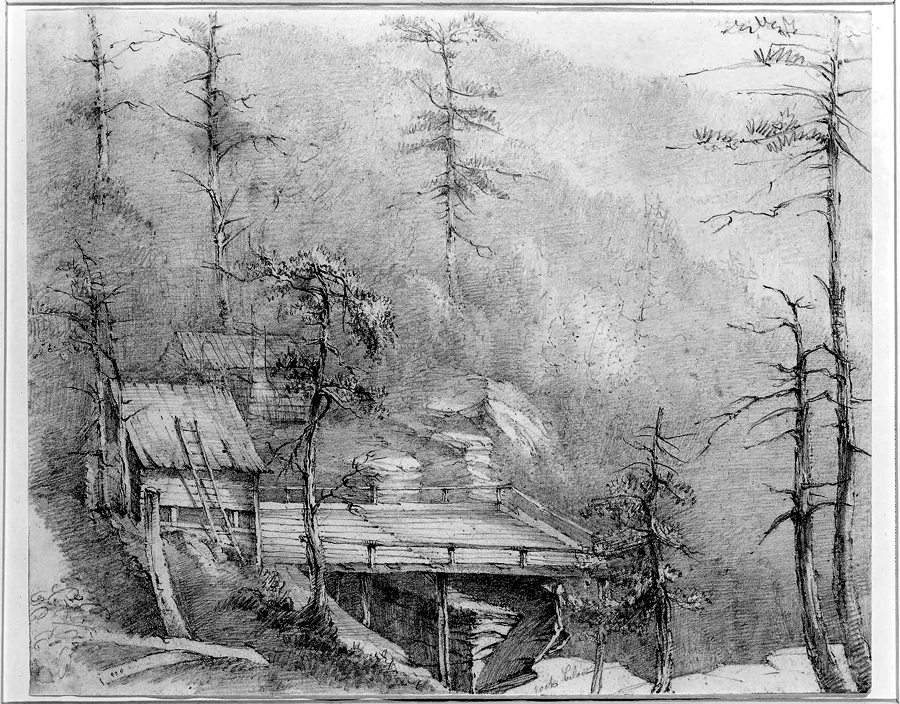

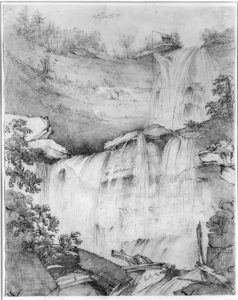

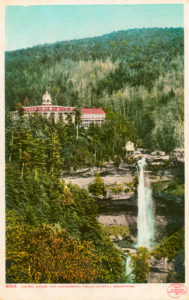

In 1825, a fellow by the name of Peter Schutt acquired a piece of property in the still-wild woolly wags of the Catskill Mountains. The purchase included a prominent waterfall. Two years earlier, the novelist James Fenimore Cooper published a description of these very falls in a bestseller titled The Pioneers. “Why, there’s a fall in the hills,” effuses Natty Bumppo, “where the water of two little ponds that lie near each other, breaks out of their bounds and runs over the rocks into the valley. The stream is, maybe, such a one as would turn a mill, if so useless thing was wanted in the wilderness. But the hand that made that ‘Leap’ never made a mill.” To be sure, other hands were more than happy to make a mill. By the time Peter Schutt arrived, a sawmill and dam had been installed just upstream from the falls. Here the lumber for the Catskill Mountain House was milled. When the hotel opened in 1824, guests were able to sit in their rockers on the porch and read their Cooper and afterwards take a stroll down the path to the falls, where—from perches lofty as they were precarious—they might gush forth grandiloquently themselves over the fabulous scenery. All the place needed, figured Peter Schutt, were a few upgrades to provide for the safety and comfort of the visitors. And so he built an observation platform and “refreshment pavilion” on the very brink of Kaaterskill Falls.

It was a shrewd business move. Having made the arduous pilgrimage to the falls, tourists were in need of a pick-me-up—often desperately so—and Schutt was happy to cater to them. Many a travel writer over many a decade spilled many a bottle of ink describing the genial scene. Once Schutt had his pavilion in place, a free and open view from the top of the falls was no longer available to the casual hiker. To make matters more tricky, the dam was now being used to control the flow of water over the falls, which in summertime under ordinary conditions often dried to a mere trickle. Visitors in times of drought witnessed little more than the ghost of a waterfall. One commentator in the 1880s likened it “to a dry smoke without lighting the cigar,” and another said “it certainly had the sanitary advantage of not being damp.” But now with these crafty innovations, visitors who desired a proper encounter with the falls could have it almost any time they wished—for a fee. Fork over twenty-five cents and Mr. Schutt would “let off the water!”

To make arrangements to see the falls, visitors would enter “a very pleasant sort of café, where”—according to one writing in 1854—“you may strengthen your physical man with any species of refreshment, from brandy-punch . . . to a cooling ice-cream or a draught of sparkling lemonade.” You were invited to register your name in a big ledger. Next, you procured the services of a guide to lead you down a series of rickety steps (installed by Schutt) to the base of the upper falls—180 feet below the refreshment pavilion—and then along a narrow path at the back of the cavern beneath the falling torrent to the opposite side of the stream. At that point “you may make a signal to Peter Schutt, who will be looking over the piazza of his café above, and if you have duly settled between you the telegraphic alphabet . . he will attach a basket to the projecting pole, and incontinently there will descend sundry bottles of the very coolest Champagne of which the vineyards of France ever dream.” For the next half hour or so, you might “imbibe Neptune’s nectar” while relaxing on a “mossy couch.” When feeling sufficiently tipsy, you once again would signal Mr. Schutt. This time he “lets off the water.” Kaaterskill Falls would then arise—or rather, descend—from the dead, however briefly, in all its torrential glory. Once the water behind the dam was exhausted, that was it—the show was over, until the pond had a chance to re-fill and another two bits were forked over. In a dry year, that might take a day or more. “I’m real sorry,” Peter Schutt said then to his guests, “but there’s just been a party here and taken all the water.Perhaps I could interest you in more Champagne.”

Although some commentators lamented this egregious exploitation of Mother Nature—”the once free torrent is now chained by the cold shackles of the spirit of gain”—by and large visitors were pleased with the hospitality offered by Peter Schutt and his family. In 1862, an affable man opined: “The damming up of the water, so much deprecated by the romantic, strikes me as an admirable arrangement. When the dam is full the stream overruns it, and you have as much water as if there were no dam. Then, as you stand at the head of the lower fall, watching the slender scarf of silver fluttering down the black gulf, comes a sudden, dazzling rush from the summit; the fall leaps away . . . bursting in rockets and shooting stars of spray on the rocks, and you have the full effect of the stream when swollen by spring thaws. Really, this temporary increase of volume is the finest feature of the fall.” Once again, it would seem, art had improved nature.

Those days of champagne and pay-per-view displays of Kaaterskill Falls are long over. The place is under much stricter management since the 1960s. I got to wondering how things were playing out this summer, what with all these recent upgrades that the state has made to enhance “visitor experience.” So I drove over to have a look.

It was hot that morning. The parking lot at the end of Laurel House Road was empty of cars but strewn with a busy weekend’s offerings to the litter gods. I parked in front of a pair of comfort pavilions, housed themselves within another pavilion, this one more rustic looking. Affixed above its lintel was a formidable sign that read: “If you carry it in, carry it out!” It looked like nothing so much as a gate to the underworld. I hurried past and made my way down the gravel path toward the falls. Other signs—nailed randomly to dying trees—begged visitors to “stay on marked trails” and “leave no trace.” I stopped to take a few notes and pictures. That’s when I looked down and observed a sizeable specimen of dog excrement, neatly bundled in a pink plastic bag. Sinister droplets of moisture had formed on the inside of the bag, alarmingly expanded with gases from having lain out in the sun. As for me, I admire those who pick up after their dogs—I just wish they’d pick up after themselves.

It was hot that morning. The parking lot at the end of Laurel House Road was empty of cars but strewn with a busy weekend’s offerings to the litter gods. I parked in front of a pair of comfort pavilions, housed themselves within another pavilion, this one more rustic looking. Affixed above its lintel was a formidable sign that read: “If you carry it in, carry it out!” It looked like nothing so much as a gate to the underworld. I hurried past and made my way down the gravel path toward the falls. Other signs—nailed randomly to dying trees—begged visitors to “stay on marked trails” and “leave no trace.” I stopped to take a few notes and pictures. That’s when I looked down and observed a sizeable specimen of dog excrement, neatly bundled in a pink plastic bag. Sinister droplets of moisture had formed on the inside of the bag, alarmingly expanded with gases from having lain out in the sun. As for me, I admire those who pick up after their dogs—I just wish they’d pick up after themselves.

I resumed my walk and arrived at the lip of the falls. None of the human-made features from the glory days of Catskill Mountain tourism survive. Gone are the dam, the observation platform, and the refreshment pavilion. One consolation: the DEC’s newly-installed observation platform, which sits just a short distance from the site of the former platform and pavilion. By the time I reached this new vista, I could have used a glass or two of old Peter Schutt’s cold champagne. I was not alone in my thinking. On the railing of the platform was an empty plastic flagon. Another one had been tossed nearby in the weeds. Just past that was a empty bottle of something called Panther Sweat. If only I had gotten here earlier, I might have seen something like the ghost of a refreshment pavilion.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on August 10, 2018