The Greene County Nuclear Power Plant

By the early 1970s, the subway system in New York was consuming enough electricity to warrant its own nuclear generating station. The Power Authority of the State of New York made plans to build it—98 miles north of the city in the town of Catskill. Estimated cost: 1.8 billion—which is about 8.4 billion in today’s dollars. The 284-acre site for the proposed plant was adjacent to a large embayment on the Hudson known as the Imbocht, long recognized as one of the most charming sections of the river.

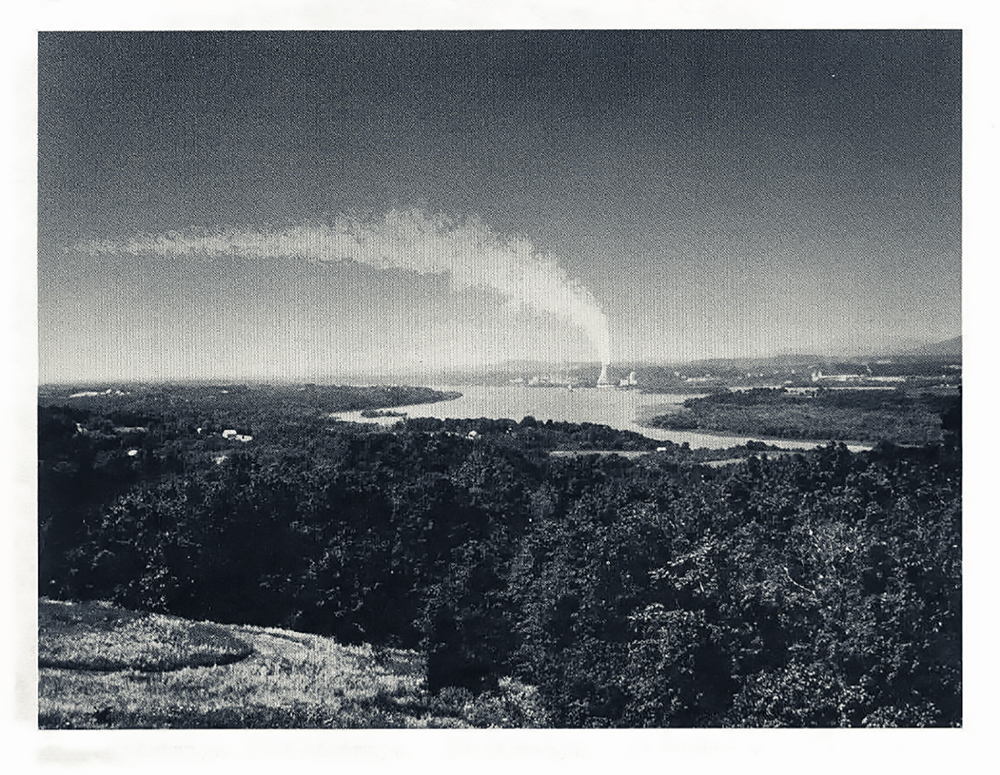

This location was a great favorite among 19th century travelers and landscape painters. Frederic Church was so taken by the Imbocht that he built his house and studio on a prominent hill five miles to the northeast, where he would have a direct and pleasing view of it. He painted this scene—which he named “Bend in the River”—dozens of times. In the early decades of the twentieth century, cement factories began popping up along the Imbocht. Their smokestacks sent long white plumes into the sky. These were clearly visible to guests rocking away in their chairs on the piazza of the famed Catskill Mountain House, situated on the Great Wall of Manitou seven miles to the west. It did not take long for the cement-makers’ vaporings to become a familiar feature upon a landscape that Thomas Cole envisioned as “steps by which we may ascend to a great temple, whose pillars are those everlasting hills, and whose dome is the blue boundless vault of heaven.” The feathery fingers of industry were still there reaching heavenward even after the Mountain House was burned to the ground in 1963. Now in the latter decades of the twentieth century, a nuclear power plant was about to be nestled among those venerable cement factories.

Plans for the Greene County Nuclear Power Plant included a 450-foot tall cooling tower along with a 205-foot domed reactor containment building. The reactor itself was to be designed and built by Babcock & Wilcox, the firm that had recently supplied reactors for the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in Pennsylvania. Writing in that discreet style of government documents, the authors of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s 1979 Environmental Impact Statement lay out how the proposed Greene County Nuclear Power Plant “will employ a pressurized-water reactor to produce a warranted output of 3600 MWt. A steam turbine generator will use this heat to provide 1191 MWe (net) of electric power capacity. The exhaust steam will be cooled by a closed-cycle system incorporating a natural-draft cooling tower using makeup water from the Hudson River. Blowdown from the circulating water system will be discharged into the Hudson River.” Furthermore, “if the radioactivity level is above the predetermined value, the distillate will either be passed through the waste demineralizer, sampled, and released to the Hudson River or returned to the drain tanks for reprocessing.” As for the region surrounding the proposed plant—a setting historians have long referred to as the “birthplace of American Romanticism”—the authors of the Environmental Impact Statement offer this laconic description: “The area within 10 miles of the site contains 23 educational, 4 correctional, 9 health, and more than 50 public and private recreational facilities. Major recreational or historical facilities attracting a significant transient population are the Catskill Game Farm, 8 miles NW of the site; Olana National Historic Site, 6.4 miles NE of the site; Catskill State Forest, 6 miles NW of the site; and Clermont State Park, 4 miles S of the site.” No mention of any steps ascending to a great temple.

Perhaps not surprisingly, those living in the vicinity of the proposed plant were not keen on the Power Authority’s plan to replace the region’s iconic figure of Rip Van Winkle with Reddy Kilowatt. As summarized by landscape architect Carl H. Petrich: “From the local resident’s perspective, the Greene County Nuclear Power Plant appeared to be highly unwelcome and inappropriate.” Even the County Legislature—traditionally the most vocal proponent of any scheme to create jobs—went on the record, several times, denouncing the proposed plant. On October 22, 1974, the legislature went so far as to pass a unanimous resolution opposing certain names for any proposed power plant within Greene County. “Whereas, it would not be in the best interest of the resorts or recreational businesses within the county if the name of the proposed power plant incorporated by reference any words which geographically, historically, or traditionally would be associated with any person, place, or thing within or relating to Greene County, such as ‘Rip Van Winkle,’ ‘Greene County,’ or the ‘Catskill Mountains.’” One might imagine that—had the plant been built—the Power Authority might have opted to leave the facility nameless, in hope that it might just fade away from hostile public attention. After all, “a name”—as they used to say—“is knowing.” But the Greene County Nuclear Power Plant was never built. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission recommended the Power Authority’s application be rejected. And so it was.

Nearly forty years have passed since the plug was pulled on the project. Since then, the Catskill Game Farm has disappeared from the landscape, the cement plants along the Imbocht have fallen into desuetude, and Thomas Cole’s house in Catskill has become a National Historic Site. Fewer people each year remember a time when those in charge thought it a good idea to build a nuclear power plant in the middle of one of the nation’s most cherished cultural landscapes. Of course, nothing stopped all those brightly-lit gas stations and strip malls and big box stores from encroaching upon the landscape—not to mention the sizable, gas-fired power plant in the town of Athens. Despite all that, nature is rapidly reclaiming the extensive swaths of land along the Imbocht formerly occupied by the cement makers. The forest is thickening and wildlife is flourishing. This erstwhile industrial site has become a de facto nature preserve. You might be tempted to have a look around the place for yourself. Best to hold off on that. For the time being, miles of imposing chain-link fence topped with razor wire discourage visitors from entering the enclave. Security guards are said to monitor the area. Pilgrims enter these precincts at their own risk. Yet do not be discouraged. As Thomas Cole expressed it in 1837: “We are still in Eden; the wall that shuts us out of the garden is our own ignorance and folly.”

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on June 22, 2018