Maurice Gans #1

In May of 1882, William Morris Davis—acclaimed geographer and avid hiker—addressed a gathering of the Appalachian Mountain Club in Boston. The subject of his talk was the geology of the Hudson Valley. He opened with some remarks about tourists in the Catskill Mountains. “Perhaps a few of these visitors may have a dormant interest in geology that needs but a little touch to awaken it into activity; perhaps some who have not yet visited this attractive region may care to look below its surface when they go.” It’s safe to say that no visitors to this region have taken Davis’s words more to heart than those men who came to the Catskills in the 1950s to pursue dreams of natural gas.

On October 7, 1958, a begrimed crew of men was operating a 30-foot-tall drilling rig on a farm in Windham. They had been laboring here for nearly ten months. On that golden afternoon, they were listening to a broadcast of the fifth game of the World Series. In the course of his duties, the keeper of the official drilling log used the corner of one page to keep score—both of the game and of the well’s progress. On that day the drill had pierced through seven feet of limestone associated with what geologists call the Trenton formation. Noted too by the log keeper was Gil McDougald’s homer in the bottom of the 3rd inning and the additional six runs scored by the Yankees in the bottom of the 6th. It would appear that the log keeper’s fervor for a Yankee victory over the Milwaukee Braves was on par with his hopes of striking it big in natural gas.

were listening to a broadcast of the fifth game of the World Series. In the course of his duties, the keeper of the official drilling log used the corner of one page to keep score—both of the game and of the well’s progress. On that day the drill had pierced through seven feet of limestone associated with what geologists call the Trenton formation. Noted too by the log keeper was Gil McDougald’s homer in the bottom of the 3rd inning and the additional six runs scored by the Yankees in the bottom of the 6th. It would appear that the log keeper’s fervor for a Yankee victory over the Milwaukee Braves was on par with his hopes of striking it big in natural gas.

The property—a couple hundred acres of gently sloping, untended farmland situated at the foot of Mount Hayden—was showing signs of being reclaimed by forest. Lush pastures with fragrant swaths of thyme had given way to scruffy hardhack and riotous Joe-Pye weed. Nary a cow was to be seen anymore on these lands. According to a story that appeared in the Windham Journal, the farm’s owner—one Maurice Gans—was not a member of the local community, but instead was “in the advertising specialty business and resides in the Bronx.” An old eight-room farmhouse that stood close by the road was unoccupied and becoming ramshackle. Gans “had planned to start a beef ranch on the property but halted plans when the war started.” The years passed and he lost interest in the place. But by the mid-fifties, the promise of abundant natural gas had reawakened his dream of turning a profit from his little place in the country.

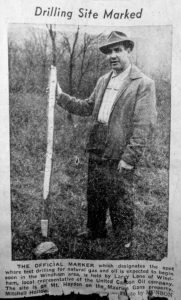

The wildcat project—referred to in state drilling records as “Maurice Gans #1”—had commenced with great fanfare on December 17, 1957. Windham supervisor Larry Lane had posed for a newspaper photo, standing on the spot where a hole was about to be bored to a planned depth of 7000 feet. The company sponsoring the work—United Carbon of Charleston, West Virginia—was prepared to spend up to 200,000 dollars on the operation. Already they had leased gas exploration rights on 35,000 acres in the Windham area. “Money,” they were assured, “is everywhere. Just let us drill for it.” If commercial quantities of gas were to be found on their property, landowners would receive eight percent of the profits—estimated to be 40 to 50 dollars per day. There was talk of the Mountaintop becoming the “new Oklahoma.”

Hopes were running high when, early in the morning on May 16, 1958, the drillers were startled awake by a “big noise” coming from the bottom of the hole. At this point it had reached a depth of 4,581 feet. Subterranean clamor was followed by the telltale odor of sewer vapors rising from the well head. Gas had been struck! Apparently a substantial quantity of it, coming in at a level two thousand feet above where geologists had predicted it would be found. The estimated initial flow was 3 million cubic feet per day, a most promising prospect—especially for Mr. Gans, who stood to receive about a hundred dollars a day from this well once its gas made it to market. The flow was so strong that the drill crew struggled to get a cap into place.

Hopes were running high when, early in the morning on May 16, 1958, the drillers were startled awake by a “big noise” coming from the bottom of the hole. At this point it had reached a depth of 4,581 feet. Subterranean clamor was followed by the telltale odor of sewer vapors rising from the well head. Gas had been struck! Apparently a substantial quantity of it, coming in at a level two thousand feet above where geologists had predicted it would be found. The estimated initial flow was 3 million cubic feet per day, a most promising prospect—especially for Mr. Gans, who stood to receive about a hundred dollars a day from this well once its gas made it to market. The flow was so strong that the drill crew struggled to get a cap into place.

News of the gas strike spread quickly around the Mountaintop. As reported in the Windham Journal: “Undaunted by a treacherous, muddy approach to the drill site, dozens of sightseers drove up to see what was going on. Several cars got stuck.” But who cared? Soon everybody around here would be able to buy a new car! Or maybe not. According to the newspaper account, a “conservative note was sounded, by Cliff Howard, who works at Sokoll’s Garage, Windham, and was raised in the Oklahoma oil and gas country: ‘I saw lots of wells out there, and lots of poor people too.’” His laconic remark was greeted with affable boos and pshaws from the crowd. Alas, those boosters of gas would have done well to heed their neighbor’s gentle admonition.

Within 24 hours of the well’s initial “big noise,” the booming flow of gas dropped off to a “gentle hiss,” estimated to be a mere 100,000 cubic feet per day—far below the level required for commercial viability. A few days after that, the gas stopped altogether. Bewildered looks were exchanged and drilling resumed. James B. Hamilton, the land lease representative for United Carbon, took a moment to share his thoughts on the situation with a group of now-anxious stakeholders: “We haven’t determined what we’ve got, one way or the other. We can’t tell whether it’s a puff or something substantial.”

And so the drilling continued—under increasingly difficult geological circumstances. The rock samples coming up did not look promising. On top of that, the well began to fill with salt water. Bailing efforts proved ineffective. Soon four thousand feet of brine filled the shaft. Nevertheless, drilling progressed through the summer and into the fall, past the World Series and the Yankees’ ultimate victory, through the holidays and into the early months of 1959. At last, on March 11th—having reached a depth of 7,185 feet—drilling at “Maurice Gans #1” came to an end “when the 1400 pound drill bit struck the hard shell of the earth’s crust.” They had hit the billion-year old “basement” rock that underlies most of New York State. For gas men, this lithic horizon is the ne plus ultra.

efforts proved ineffective. Soon four thousand feet of brine filled the shaft. Nevertheless, drilling progressed through the summer and into the fall, past the World Series and the Yankees’ ultimate victory, through the holidays and into the early months of 1959. At last, on March 11th—having reached a depth of 7,185 feet—drilling at “Maurice Gans #1” came to an end “when the 1400 pound drill bit struck the hard shell of the earth’s crust.” They had hit the billion-year old “basement” rock that underlies most of New York State. For gas men, this lithic horizon is the ne plus ultra.

Over the following weeks, the steel casing was removed from the well. Concrete was poured into the hole and fieldstones were piled on top. The drilling crew and their derrick moved on to more hopeful pastures in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Decades later, the former drill site was acquired by the state and added to the Catskill Forest Preserve. Henceforth it shall remain “forever wild.” All trace of the failed Maurice Gans #1 well and the insubstantial dreams that went with it have vanished—save for a lichened heap of rocks in a lonesome wood.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on April 13, 2018